Appropriately, the American historic preservation advocate Richard Moe once said, “Preservation is simply having the good sense to hold on to things that are well designed, that link us with our past in a meaningful way, and that have plenty of good use left in them.” For those of us who live in the historic neighborhoods of Riverside or Avondale, or those who pass through to admire the charm and beauty of the original architecture, walkable streets, and river vistas, it’s very easy to forget that what we love about this area did not appear magically overnight. When we are fortunate to drive its streets every day, we can become accustomed to our surroundings and take for granted its uniqueness.

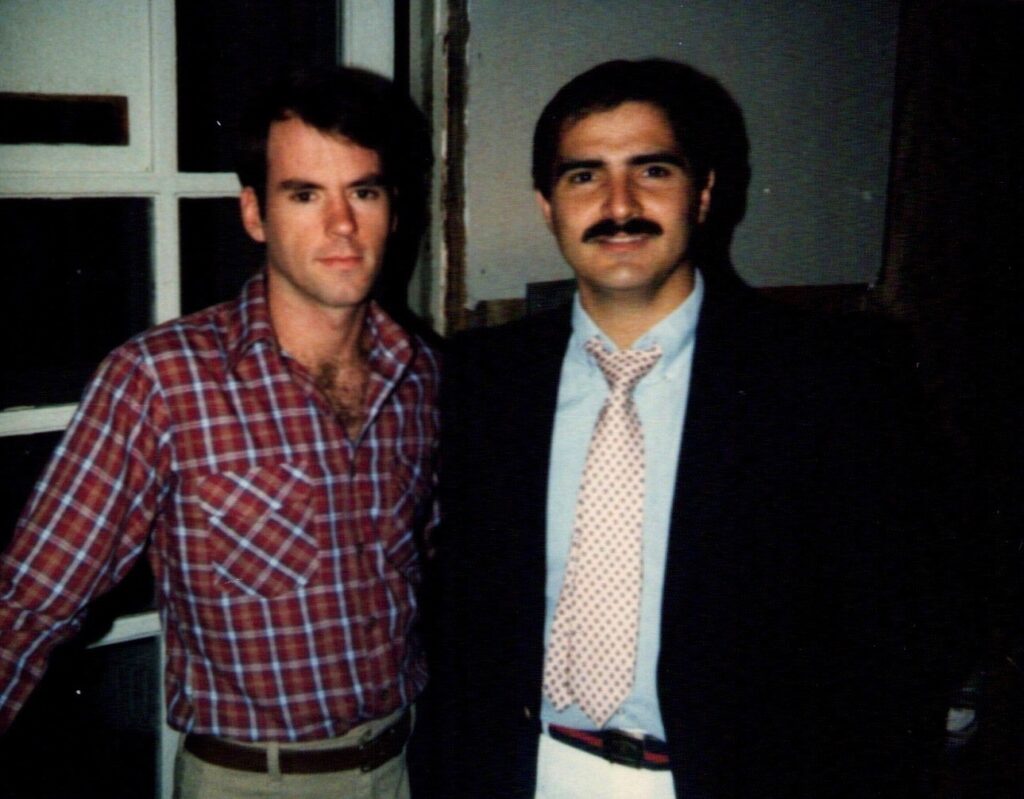

Tony in front of Richard Ceriello’s renovated home, c. 1990.

Thankfully, we have long-time residents like Richard Ceriello who remember the neighborhood before Riverside Avondale Preservation existed (1974) and other protections, such as the historic overlay and the Jacksonville Historic Preservation Commission (1990), were in place, before many of today’s most stunning structures were restored to their early 20th-century glory. Richard has seen firsthand the slow transformation of the neighborhood over the years, and when he thinks back, there is one person in particular whose legacy he cherishes.

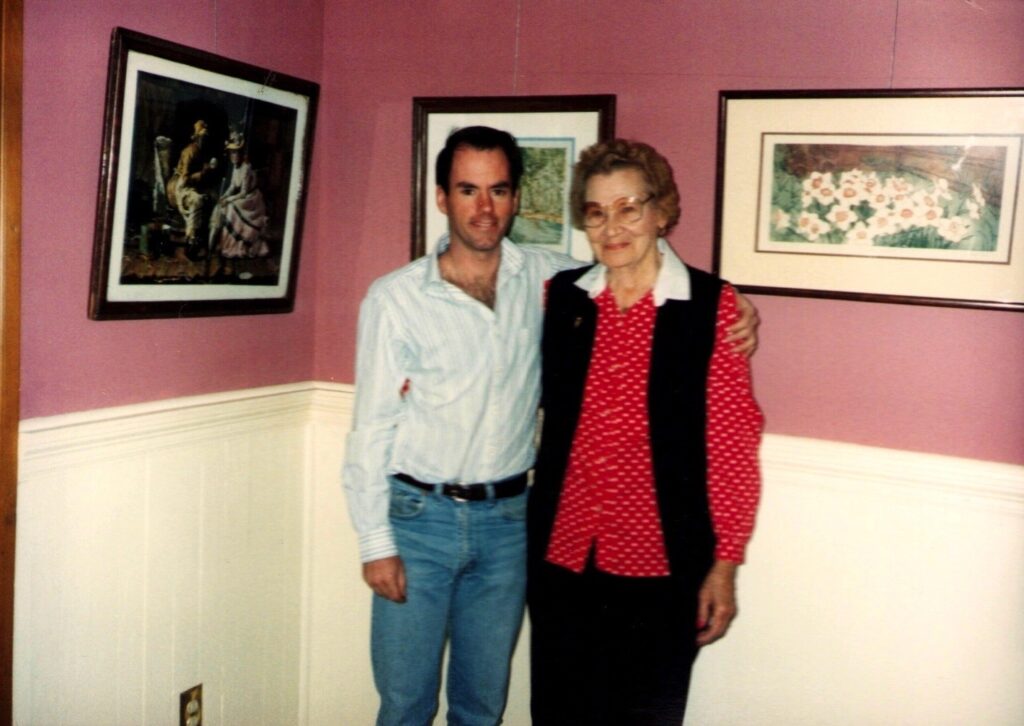

Left to right: Tony and Richard c. 1990; Tony and Iris Lightbody Harris c. 1990.

Anthony “Tony” F. O’Connor was Richard’s partner for 12 years, who passed away from AIDS-related diseases in 1995 at the untimely age of 33, but the magnitude of Tony’s kind spirit and generosity toward his community far surpasses the brevity of his human life. After he received his HIV-positive diagnosis, Tony was inspired to plant as many trees as possible along the then barren and neglected Riverside streets. With the help of Richard and landscape architect Scott Dowman, among many others, Tony’s vision came to fruition, both before he died and posthumously.

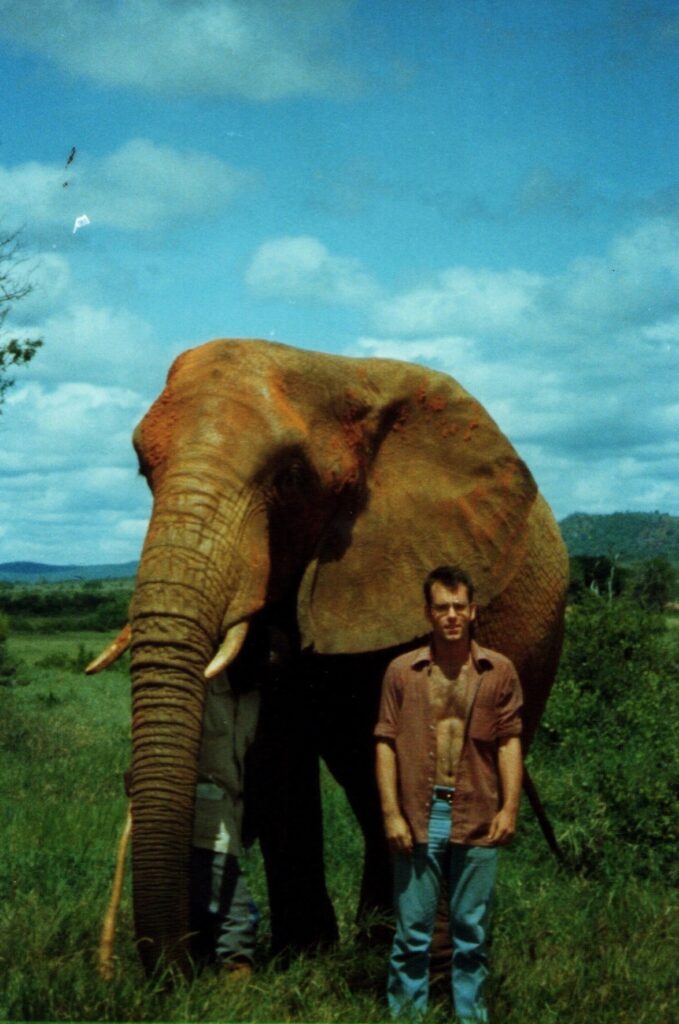

Tony on safari in Kenya c. 1983.

All in, it is estimated that Tony’s Trees is responsible for 500-plus trees planted in Jacksonville, primarily in Riverside and Avondale. The attractive tree canopy we all enjoy now is in large part due to Tony’s desire to leave a gift for the neighborhood he loved. RAP is pleased to honor Tony with our first oral history project. Listen below, and/or read the transcription, to our interview with Richard and Scott. They speak in depth about Tony, but also about Riverside in the 1970s and ’80s, as well as the history of the LGBTQ community in Riverside.

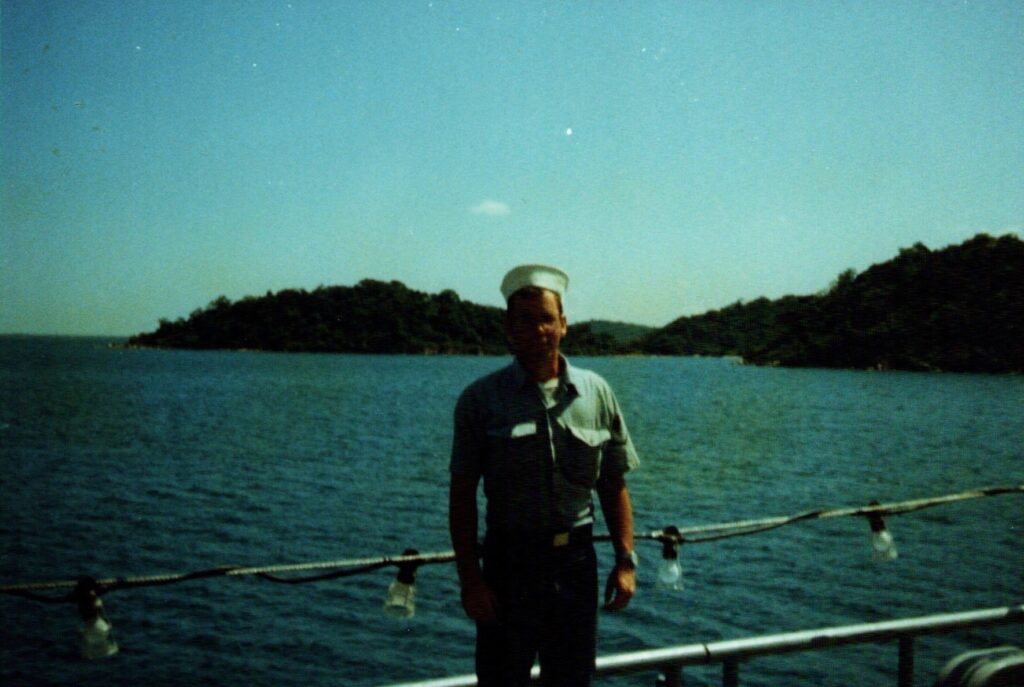

Tony in the Navy, Sri Lanka, c. 1981.

Transcription below:

RAP Archivist: This is the first oral history of Riverside Avondale Preservation about Tony’s Trees. It is Monday, November 17, 2025, at 3:11pm. And I’m going to ask my two guests to introduce themselves.

Richard Ceriello: First, Richard Ceriello, having been here in Jacksonville since May 14, 1976, now almost 50 years.

Scott Dowman: Scott Dowman, I moved here to start first grade in 1965, lo and behold, and I have been here since and went to the University of Georgia. But wanted to return, because I love Jacksonville so much. So it’s good to be here.

Archivist: Thank you for coming to our beautiful Buckland House to talk about Tony’s Trees and Riverside Avondale and how Tony has impacted us to this very day. Richard, you told us you moved here in 1976, so you’ve been living here for many years. What brought you to this neighborhood, and why did you stay all this time?

Richard: Oh, that’s a really good question. I came here in 1976 just for a year. I worked at the Speech and Hearing Center in downtown Jacksonville. I was dating somebody in New York, and I planned on going back to New York. And in fact, that year, that first year, I was going back and forth to New York all the time. My profession required me to do a clinical fellowship year; it’s kind of like a internship, or that sort of thing, you know—a period of time in the hospital, a clinic. And so I was at a clinic downtown. I was there accumulating the necessary hours. A friend of mine had already moved here. We went to graduate school together, and she recommended me.

It’s an odd story. Monday morning, I got a phone call from some woman with a Southern accent. I was preparing to go to work in Bloomingdale’s, where I was working on Long Island, and I get this call, and you know, “Mr. Ceriello, like to invite you to come down to Jacksonville, Florida.” Well, I’ll tell you, I never heard the Southern accent before, and so I thought it was a joke. And I said, “How did you find out about me?” She said, “Well, Sandy, Sandy Epstein Simone, recommended you. I said, “Oh, goodness gracious. I just saw her. We graduated from graduate school together.” I said, “Put her on please, because I don’t want to be punked and find myself in an airport in Jacksonville. And then somebody call me and say, ‘Hahaha, I’m joking.’”

Anyway, so I accepted the offer to fly down. I flew down that Wednesday, [got] picked up at the airport, shown the clinic, shown the city, and they asked me if I wanted the job. And I thought, Okay, yeah. Why not? I’m adventurous. So within about a week, I was on my way to Florida. My mom and dad knew I was [going], but nobody else did. And so they probably were expecting me to float down the East River, I think, my face down, knowing my lifestyle in those days. So I came here with the understanding of only staying a year. And so one year became two, and then I got a job offered back in New York, but they were paying me the same money I was making here. And I started thinking, you know, A dollar in Jacksonville goes a lot further than a dollar in New York City.

And so at the same time, about the late ‘70s, I got a job at St. Vincent’s as a speech pathologist. So I was commuting from Baymeadows, and it was just a bit of a trip early in the morning, and then trying to get into Riverside in the morning. So my friend Sally Suslack, who was an early member of RAP, had recommended… she said that St. Vincent’s owned a lot of property in the area, and perhaps I can get an apartment through St. Vincent’s holdings. And so that didn’t work out exactly as I planned, but I found an apartment right near St. Vincent’s on St. John’s Avenue. Moved into the neighborhood in ’81, started making a few friends. I’d already had a bunch of friends anyway, but I was making a lot of friends. The neighborhood was very much more LGBT concentrated in those days because it had not been fully gentrified, and the prices were very reasonable for a lot of hippies, musicians, gays, you know, the marginalized population. And so found a nice apartment and got involved in RAP.

I got involved in RAP through… [her] name was Pat Escajeda. But she asked me to attend an event that RAP House was having, hosting. And I said, “Okay, I’ll bring you.” And we were friends already. She was a neighbor of mine, so we went together. And I was being introduced to the board of directors of RAP, and Sam Eisenberg, who was, at that time, I think he was chairman of RAP, the board of directors. And he said, “Would you like to be among the best people in the city?” And I thought, well, I’m rather suspicious of any group that would have me. And so I said, “Sure, you know, why not? That’d be great.” And they invited me to be on the board of directors. That was in, you know, the early ‘80s—’81, ’82, somewhere around that. And started chairing little events, like the bicycle tour, the haunted house we had, the art festival, the Home Tour… things this that and the other. [I] moved up through the structure of RAP, from what we used to have as a “super board,” which was 50 people. Then they had the executive board, which was the officers. And so [I] moved up in that, and I was Vice President. Tom Purcell was President. Good man, really a fine man, helped me out, was a real mentor. I became President in ’86, Chairman of the board, and about that same time, in ’85, I bought the house that I’m currently living in.

I’d met Tony a few years before that. That’s Anthony F. O’Connor from Shawnee, Oklahoma. He was in the military. I met him at a bar on the other side of town through a friend, and he was just such a cutie, such a cutie. But he was wounded by his religion and being gay, and I took a real liking to him. And so this is in ’83, I bought my house in ’85, and I bought it quite honestly because Tony liked it. I was a party boy prior to that, and I just didn’t want to be tied down with either a boyfriend or a house. But they came about the same time, and that house really spoke to me. Tony really liked it. There was a porch on it that he liked, and it was kind of a blank canvas I wanted to create something with. So bought it in 1985, and I’d asked RAP to… give me some money through their evolving fund, and they were willing to do that. It was a rather high interest rate, and Tom Purcell, the President of the board—this is information that’s very unknown to most everybody—but Tom Purcell pulled the money out of his children’s trust fund and gave me… he bought the house for me. And for the first few years, I paid him only interest until we got the house up to a level where we can go conventional financing. Because it was condemned, and banks were not necessarily receptive to holding mortgages in Riverside because it was not yet… it was still really kind of a rough neighborhood. And bless Tom’s heart he did that for me, took a bit of risk. He certainly was a rich man. He didn’t need the house. He could have spent his money on something else, but for those years that Tony and I worked on it, I paid Tom at monthly interest payment. Worked out just fine. Then we went conventional financing. That was fine, and ended our business relationship.

Tony and I were together around 1986. I had been seeing things happen with his health that concerned me, and he was getting these opportunistic diseases which men of 23 or 24 years old were not getting. And he had a worst case of Cat Scratch Fever his doctor had ever seen; he was almost hospitalized and getting, you know, wounds that just didn’t heal very quickly. And I said, “I think it’s time for you to get tested.” And just about that same time, his previous boyfriend had just died. And I said, “Yep, it’s time for you to get tested,” and we found out that he was indeed HIV [positive]. So we kept him alive for those 12 years. That was remarkable in those days, because you would die fairly quickly after the diagnosis, because your body was pretty well wracked by all these other diseases that came along. But he had those 12 years, and so during that period of time, when he got closer to the end, realizing that he was terminal, he wanted to do a gift for the neighborhood. And he wanted to give the neighborhood trees, because where he came from in Oklahoma they had lost all of their American elm trees because of disease, and he remembers all the skeleton remains on the sidewalk. So I introduced him to my friend Scott Dowman, and Scotty and he started a wonderful friendship. And I’ll let Scott tell a little bit about that.

Archivist: Scott, can you tell us a little bit about how you came to Jacksonville and your connection to Riverside Avondale? And then talk to us about Tony.

Scott: My dad moved here to take a position, and we had to live at Jacksonville Beaches, or Mayport, to rent a house because Arlington was building so quickly, there were no homes for sale. Long story short, I loved the trees that were here. We came from South Georgia, but it was different in the water. But I remember coming in in the second grade to the old children’s museum, which was in a mansion on Riverside Avenue about where the Blue Orchid is [now], I think. But coming to that, I saw houses like I had never seen before, and that was my very first experience. And then we traveled across the bridge to the new friendship fountain and went around that… the children’s museum was not there [yet]. My second connection with the neighborhood was I was a clothing salesman for La Tierra, and remember La Casa Ropa? There were two high-end stores in Riverside, and I rented an apartment nearby for $100 a month. It was well worth that, actually not, but still, Riverside was the friendliest place you could come and live more freely. Springfield at that time was a little too dangerous, and all other neighborhoods were out. So the summer that you had the first picnic, I remember I didn’t attend because I was afraid I would lose my job at my store.

Richard: ’78.

Scott: 1978—that was it. I was not as afraid of my parents finding out as I was my employer, because I would have been fired, you know, for that.

Archivist: And this picnic was… can you tell me more about the picnic?

Scott: The pride picnic. It was in Willowbranch Park.

Richard: Right, yeah.

Scott: It was attended by about 100 people.

Richard: Yeah, about 300.

Scott: Was it?

Richard: Yeah, 300.

Scott: My friends went because we were friends from going out. We had two gay bars then. One of them was tiny, and the other was tinier. And they were all pushed back into industrial areas, but we survived, I guess, the assault on the gay bars by First Baptist Church. We became friends and we… Yes, we did. We socialized and danced together.

Richard: Kathy Mead…

Scott: Kathy Mead was our connection.

Richard: Arthur Findley and that whole group, wonderful people.

Archivist: This is in the ‘80s?

Scott: Late ‘70s, ’78 and ’79, right? Couple years.

Richard: ’80, ’81, yeah, they’re about that, right?

Scott: I got a chance… And one thing, I know this is an aside, but I’m just trying to think of all my connections, even though I only lived in the neighborhood once. I got to do a color rendering when I was doing an internship at RS&H of the first tree planting along Riverside near St. Vincent’s—the one that’s now a domed, beautiful canopy and all the way back to the museum. And I think it was Susan Fisher, but I remember rendering that for presentation, probably to either RAP or St Vincent’s, because I think Greenscape did that…

Richard: Yeah, as a side note. Susan Fisher was one of the two founders of Greenscape. I just stumbled across her about a week ago. I have her current phone number so we can include her at another point. But she had an idea of reforesting, or.. you know, reforesting Jacksonville’s urban core.

Scott: That’s, that’s what brought me here. I’ve gone on the tours. I love Riverside, even though I live in outer San Marco—poor man’s San Marco next to Bishop Kenny, South Shore. But I love the neighborhood, and I’ve come to love the people. But when I met Tony, I was so impressed by his… he was very real. He had a real passion for trees, and he knew about them. And I was just, I thought, This is amazing, you know, to meet somebody. He was, I’m trying to think if I was about his age. I can’t remember. I was probably 31 or 32. He might have been a little older.

Richard: Well, he died when he was 33. So that was in ’95.

Scott: Yeah, he’s a little younger. So anyway, I loved him, and we… I think we plotted out some trees. We walked and did some flags, and he helped me with the placement of the trees. And I think we went by the guidance either of someone with Greenscape, but it was really Tony who began it.

Archivist: And where did y’all first start planting?

Scott: I think right out here.

Richard: From Acosta to Cherry. Acosta to Cherry on Herschel. And he used his own money. We didn’t… he didn’t… We didn’t tap into… He was asked… We did have a fundraiser here at the at the RAP House. They had a little fundraiser here. There was some money given by some of the neighbors who were having trees and put in the house. But there really wasn’t very much money, but Tony mostly used his own money, and the trees weren’t particularly large. They might have been a five gallon.

Scott: They did a match against his money.

Richard: Later on. That was after he died, yeah.

Scott: But there was some early support or interest from Greenscape, because they had planted Riverside Avenue, and there were no other streets planned for planting. So it was about the second. I think Stockton got done a little bit around that time, but that was a different project going out to I-10.

Richard: That’s true. If I can interject for a second… you reminded me that Tony on his own called Greenscape and spoke with Anna Dooley or Dooley’s predecessor. [Anna] came a little bit later, but her predecessor Susan Fisher… And so he said what he wanted to do. He had realized that he wasn’t going to be around for very long, so while he was still vibrant and still had some wits and physical ability to do it, they got in touch with you, or you got in touch with him, or however it happened that you were included in that.

Scott: I was asked to do a plan, draw a plan.

Archivist: So you were included, Scott, because of your artistic abilities?

Scott: I don’t know about that, but I was a landscape architect. I’m retired now. So I had done planting plans, and I had done a few. I had done an early one in Springfield, very early with Jim Watson, but they asked for a drawing, and that might have been where Susan Fisher said, “Scott, would you do a drawing of where we want to plant the trees?” Or maybe Tony and I might have even drawn…

Richard: Yeah, I’m not sure exactly, but there was another parallel thing happening at the same time, where they were putting in dogwoods on Riverside Avenue, and that turned out to be a big mistake. And then you came in, and you worked with Tony independently, maybe with Greenscape on the periphery, but it was you and he mostly.

Scott: They needed a plan to submit to the city in that time for approval. JEA I think probably were the ones at that time to sign off. I’m not sure we even had a city landscape architect that early, but if it were, it would be Fred Pope. But they were approved, and I think that’s when they started to go in. I can’t remember the size.

Archivist: What species of tree did you…?

Scott: Live oaks and, at that time, Bradford pear was a satisfactory tree. It’s still good, but it has some weaknesses. But there were live oaks, and…

Richard: Mostly live oaks at first, and then after Tony died, we did the three species—live oak, Bradford pear, and crepe myrtles.

Scott: Crepes. Yes, we did the three. Easy. They were suggested because of their ability to sustain in an urban environment and do without water if need be. You know, they’re drought tolerant.

Richard: And they were floral, you know, and they’re still on on on Park Street. In the early spring, you’ll see the Bradford pears blooming. Now, they have a lot of parasites in their branches, and they really need to be dramatically cut back, but they’re a beautiful plant. I understand Greenscape doesn’t offer those trees anymore, and also same thing with crepe myrtles. They’re not native to this area. They’re beautiful, but they also need to be heavily groomed every year. But the best, of course, is the live oaks.

Scott: If we had done nothing but those that would have been beautiful, because I see when I drove up this way, that house over there, those trees are halfway, almost three quarters of the way, across the street. So there’s a big stretch of shade now that wasn’t there.

Richard: Right. And of course, Stockton is a wonderful avenue into the neighborhood, which, you know, when they did that the tree planting and—you were involved in that, weren’t you?—that the neighborhood was saying, “Why are you wasting trees in that poor neighborhood of Riverside, because they’ll just be ruined?” Which, of course, is that classist attitude that we demonstrate when we’re not planting trees where they need to be planted. But it’s beautiful today, and the neighborhood had been gentrified. And there’s probably a direct correlation between the trees being planted and the gentrification of the neighborhood.

Scott: That was early on, and that was rough, too, because it wasn’t so much the folks around it, but just the terrain. It was ugly; it was harsh; it was hot as hell. It was dirty because there was just nothing to green it up. You could see houses like a block away that were decent, but that was just such a barren desert. And I didn’t think that they would live either, but they hired someone to come and water.

Richard: That was part of the deal.

Scott: …And tried to get homeowners to water. Some were very excited to have a tree; others were not happy because it took their parking space…

Richard: …Or they were renters, and they didn’t care, as most of that was rental.

Scott: But they took.

Richard: Yeah, they did. It looks lovely. It’s a great credit to you.

Scott: No, you. Everybody.

Archivist: I want to talk about… so you’ve talked about, like, kind of how it came together, and where you first started planting. So can you talk to me about the next phase or two? Because you’ve mentioned, after Tony passed away, there was some work still done. So can you talk to me about what happened after the initial phase?

Richard: Good question. There were three phases. Actually, the first one was with Tony and Scott. After Tony passed away and left some money through Greenscape to be… through me to give to Greenscape, which was $5,000, but I released it in installments, as we did a section. Scott and I did the first installment on streets like Park Street, because, initially, the area that Tony and Scott worked on was from, let’s say Acosta to Cherry. Scott and I continued on Herschel all the way down to Margaret Street. Then we did Park Street all the way up to, almost to Edgewood. And then we also did Oak Street, a few trees along Oak Street. We did Margaret Street from the interstate to, almost to the river, and then more trees in Willowbranch Park. We created a bit of a grove there. So those were in two installments over a couple of years, because, of course, you want to get the trees in the winter or… before they get stressed out in the hot weather. And so then, which was good, the city reimbursed every expenditure for trees 50 cents on the dollar. Yeah, 50 cents on the dollar. For every cent that Greenscape spent through this program, the city gave them 50 cents. And then also, along the way, my friends were contributing money, significant amounts of money. For instance, I think the owners of European Street gave a significant amount of money.

Archivist: How was that kind of deal—the 50 cents on the dollar—how is that negotiated with the city?

Richard: That was a relationship that Greenscape had with the city. So as I suppose, Greenscape demonstrated the expenditure; the city then reimbursed them. I remember speaking to our city councilman about it at the time, and he was asking me, “How much do the trees cost?” And I said, “Well, I think roughly $100 to $200.” And [he] said, “Oh, that’s easy, easy, easy.” I don’t think he ever allocated any money as I remember. I think he went on to become the tax assessor or something, but, yeah, that was a relationship that Greenscape had with the city.

Scott: They stepped it up, too, because they contracted after that, it was Davey Big Tree. Because you and I walked down park, when I could walk 10 blocks, and we either painted on the ground or put flags in the ground with him with us. And he would say, “No, you can’t do that here because of limes.” They then came in with the bigger spaded trees, which made an instant change. They were small. They were probably, maybe they were nine or 10 feet tall, but they were decent.

Richard: The philosophy being the right tree in the right location. So we didn’t want to put a… We put crepe myrtles under the wires because they didn’t get too tall. And where the wires are, where the street has no wires, we put in live oaks because they do have a bigger canopy.

Scott: I have a visual memory of him walking because he insisted on holding the spray stick, you know the one… because we had a can. It was actually…

Archivist: You mean Richard or Tony?

Scott: Richard. This was later, when we…

Richard: It was a power thing, you see. It was a power thing.

Scott: But we would put a dot on, and then they would come and check it either later or put a flag up. But Richard, walking down, he looked like he was totally in charge and knew what he was doing. But who would have thought that those orange dots would have become something that gives shade?

Richard: I had to appear as if I knew what I was doing, and to give me an air of knowledge, which was only superficial. But, yeah, to look at it now, I mean, even someone like Susan Fisher, who, as I said, is still vibrant and she’s living out at the beach, but she says when she drives down the neighborhood—and she was in the neighborhood last week for shopping of all things—and she said she gets inspired when she sees the oak trees especially.

Scott: Nice lady. She and Anne Baker, the late Anne Baker, were founders, I think, of Greenscape, but they they worked together on convincing the neighborhood to plant phase one, or convincing maybe it was RAP, maybe it was the city.

Richard: You couldn’t say “no” to either one of them. Susan Fisher, for naught, I mean, but they’re really very, very gracious and sweet, but steel—steel magnolias, you know. And rigid backbones. So when they had something in their mind, and I have nothing but respect and admiration for Susan Fisher.

Scott: If you can think that you were a part of something that lives, that’s kind of a legacy of theirs.

Richard: Yes, indeed. In fact, in truth, Susan and I spoke about this, and she was excited about hearing about Tony getting credit, but she also wanted to make sure that Greenscape was mentioned in your archives, because that was the avenue in which we used to get the trees in, was through Greenscape.

Scott: That’s true.

Archivist: So you talked about designing the first plan that had to go through the city to get approved. And so for the second two phases, did you have to go through that process again with the city and present a plan, or did you kind of have the ability to do what you needed to do after phase one was successful?

Scott: We didn’t have to submit a plan, which would have been very, very hard. You know, two blocks were easier, but you know what they said, because it was Davey, that Davey would be pulling the permit. So that released us, and I think they got the approval of JEA at the time to do so, but we didn’t have to draw anything. I think maybe that was why we literally marked it and then they would approve it.

Richard: Sure, yeah, it’s always wise to work with the power structure that be, but I’m also the kind of person who will apologize and not ask permission. Apologize later. “Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t know.” But the trees are going to stay. No, we were respectful in truth, and we did have Davey Big Tree Company as well as Greenscape with us. And of course, we kept RAP informed of all of the things that we were doing.

Scott: There was resistance from some businesses, because they were fearful that we were going to cover a sign. We understood that. I think we made choices in those situations. We did not do… I don’t think we went through Park and King. That was another project, unless we did.

Richard: That was another project, yeah.

Archivist: I was gonna ask if you, since you have the city approval, if you had to do any further approvals from like private residents, if you’re planting in their yards?

Richard: Yes, in fact, we, ideally, I mean Susan Fisher and I would ideally ask the homeowner—because this is city right away that we’re putting in it—but we were asking the homeowner if they would water it, and 90% of them said, “Yeah, for sure. It’s not costing me anything. I’ll keep water on it.”

Archivist: So you didn’t need their approval necessarily?

Richard: Well, you would have wanted it. But I’ll tell you, there was a house on Park Street where the owner of the property was adamantly anti-RAP. And because we were just planting trees, the first thing he asked me is, “Are you involved with RAP?” I said, “No, this is a, you know, something entirely different. This is Greenscape.” “Well, I won’t have any tree planted in front of my house if it’s because of RAP.” I said, “Listen, we have…,” and then Susan jumped in and said, “Listen, we have nothing to do with RAP. Whatever your problem is with RAP, that’s your problem. We want to plant two trees here.” And so he went on and on, and she was not going to take “no” for an answer. Those trees are in front of that property, and they’re beautiful.

Archivist: Who says “no” to free trees?

Richard: Yeah, beautiful trees. They’re really gorgeous.

Scott: People are afraid of things. It’s going to drop on my house. It’s going to block. A lot of folks at that time on certain streets were parking in the front yard, so they were pulling across that space. And we actually did plant one in front of that such thing, and [the trees] survived. I think that they got around them, but I have seen people murder trees. You can do so chemically, or you can gird it all the way around, and it’ll die, and then you can justify taking it out. I never did see anything of that nature happen, which was pleasing. People were afraid of the tree canopy. It was falling apart at that time. So the water oaks that were planted probably in the ‘20s were becoming big liabilities. So when people heard “oak tree,” it’s like, “No, you know, we don’t want an oak.” They didn’t understand the difference between the live oak and the water oak. But when that was explained, I think that they came along, and I haven’t seen a single live oak die in this neighborhood.

Richard: No, not at all, and some of them have really been brutalized by cars crashing into them. With regard to the Church of the Good Shepherd, that’s where Tony had his funeral, where we had Tony’s funeral. He didn’t plan his own funeral. We had his funeral there. And what was really cool about it, the church was full, because he had so many friends. I had a lot of friends, and, you know, that kind of thing. And so instead of having flowers on the altar, it was trees in a five-gallon root ball holder. And so Judy Higgison was a good friend of his, and she was a prominent neighbor in this community, and she had organized with the church to fill it with trees. They had organized trees to be placed in front of the altar and lining the… Louise Hardman, Louise Hardman, Louise Hartman and Judy Higginson, both prominent socialites in our community. They were friends of Tony’s, and so they both were very active in the Church of the Good Shepherd. So the main aisle going to the sanctuary was lined by trees. The actual altar was lined and decorated with trees, no flowers. And so afterwards we have the reception at my house; there might have been 150 people there. Everyone who came to the church and the reception afterwards got a tree. So they got either a crepe myrtle or a live oak or a Bradford pear. We had them lining the driveway. All you had to do is take them and walk away. And so they are now scattered all over the city, because people brought them [home], and they were living on the South Side, West Side, North Side, and they took these trees with them. So his reach, as far as tree planting, [is] well beyond just Riverside.

Scott: Riverside was more open-minded at that time, too. You know, it was the place where most creative people came. Springfield hadn’t gotten to the point that it is now, and San Marco was way too conservative, and other neighborhoods, it just… Riverside attracted more progressive, educated, artistic… And so that was kind of like a budding time where young couples thought, This is really cool to buy an old house, not to buy in East Arlington or some of the neighborhoods that have since developed. But it drew people that were open to that beauty and change and taking responsibility for your neighborhood in a way and becoming… Well, then RAP emerged. Well, RAP has been around much longer than that. SPAR emerged, probably in response to the success of RAP, but that was a long struggle for them. You know, many, many years struggling, but Riverside just came along a little faster. And then I think people became aware of protecting homes, because St Vincent’s tore down a lot of homes. This was one that I remember where it used to be, and luckily, they didn’t tear it down.

Richard: This house has always been in this location.

Scott: Is there not a home that was moved?

Richard: Yes, the old RAP House on Riverside Avenue and King right over there.

Scott: Thank you. That was my thought. But they were taking down…

Richard: It’s on Powell Place now. What they did was they backed it… took it up there at the corner of Riverside and King. There was a cluster of really big houses, and one was moved to Palm Valley, one was moved to Powell Place, which was the RAP House, and the other one was demolished, which was really tragic, because they were all perfect condition. And the one behind the RAP House, where the emergency room is for St. Vincent’s now, that was Bishop Weed’s residence, and it was on at least an acre of wooded lot on the water, and so that was amazing. You had that wooded lot next to the hospital. And after, in the mid ‘80s, late ‘80s, whatever trust the family had, the Weed family, had to protect the big house, that trust was broken by the lawyer who was handling the trust, and they sold the property. And so the [old] RAP House, though, was picked up, brought down King Street almost to the river, and backed up into Powell Place, and that’s where it is today. The front door faces out on Powell Place. I will say—funny story—that I was riding around the neighborhood with some friends, and I stopped in front of that house. And I was talking to my friends on bicycles, and the woman who owns the house came out, and I said to her, “I took a bath in your tub.” And she looked at me like, “What?” I said, “Well, it used to be the head RAP headquarters, and I didn’t have any water in my house that I was restoring, so I came over to the RAP House and took a bath in your tub.”

Archivist: Did she know it had been the old RAP House?

Richard: She knew. We laughed and laughed about it. I said, “The unfortunate thing was, there was no water heater, and so it was pretty cold water.”

Scott: I think St. Vincent’s got a lot of heat for the number of homes that they did take down, especially for surface parking.

Richard: Well, and Riverside Hospital, between the two hospitals.

Archivist: I’ve heard that was kind of the last straw, in a way, like kind of what really propelled RAP to become RAP.

Scott: It was. They started to see things that the hospital was using. They were tearing down homes to build surface parking lots. There’s one right behind us, somewhere where Kathy Mead lived. There were apartments; they were just like any other street through here, and they just bulldozed them, and then they just put in a surface lot.

Richard: Yeah, part of it was they didn’t want the liability of anybody breaking in and doing something getting hurt, so they demolished the house. But you’re right. It was for parking space, but they also didn’t want to have the liability of someone being there and getting hurt, or a house walling on somebody. Many of those houses were in excellent condition. Wayne Wood could easily tell you about that. But in the time that I’ve lived in this neighborhood, too, I’ve seen many houses come down that really had a life, a long life, ahead of them.

Scott: There was a turning point where they started making it easier to take the house and move it. Maybe they began to give it to people, that being St. Vincent’s, because they were under heat for tearing them down. And so I think they took a turn maybe with their PR and started to say, “Okay, we’ll be less offensive if we move it somewhere else in the neighborhood.” But then it slowed them down. They didn’t do too much after that. Knock on wood.

Richard: Well, they opened up another location; that was always the intent. They opened up one on the South Side. There’s Baptist way out on the South Side. St. Vincent’s has other campuses now. There was just no where else to go.

Scott: Well, they’re they’re not growing as quickly, but I think they also are a lot more sensitive to being a better corporate neighbor today than they were 30 years ago.

Archivist: I think there are also just more obstacles in place.

Richard: That’s correct. It’s a historic district now, and that’s true. Yeah.

Scott: That was key, because you were the very first in Jacksonville, correct? Or Springfield?

Richard: No, Springfield came later. Yeah, Riverside was the first. And then, of course, the thing is, the political party of that community. There’s a real division between the Republican party and property rights and Democrats and property rights. Many of them were convinced that it was a smart economic decision to vote for the historic district designation.

Scott: It failed in San Marco. I remember there was a start to create San Marco as a historic district, and it was not supported, I think because of, like you said, property rights. It was about not being able to take a house down, to build a bigger house or modify it. There’s so many homes that have come down in the last 20 years in San Marco along the river, that are now bigger houses, but they didn’t want any constraints on design and architecture. And there were a couple of big design builders that just built the hell out of the houses, but doesn’t happen here. Everything is because of that, it’s visually cohesive, it’s calming.

Richard: Right. Well, we have the overlay. But, you know, Ortega has a historic district, but it’s a national historic district perhaps, but it’s the local designation as a historic district where it becomes a powerful restraint from what they can do to their houses. They don’t have that.

Archivist: Getting back to Tony and Tony’s Trees, you’ve said a few things that kind of point to this, but I wonder if you could each talk about what you see as Tony’s legacy. What was the outcome of these trees being planted, and what it means to you now and then, and how you think the neighborhood benefits from it, even today?

Richard: That’s a very good question, very profound question. I would say, you know, Tony was an extremely modest, humble person, and it’s true, opposites attract, because I am not either. But he was such a modest, really a sweet sweetheart, and his interest was he loved the neighborhood. He had been here as long as he was with me, but prior to that, of course, he was in the Navy and he’d been traveling a lot. But I think for him, he was so happy that it would create a space that would be shaded for children to play under, habitat for birds and little animals to live in. This was really important to him, and that’s why, on his quilt, we chose a tree, because he thought in his—he’s Potawatomi Indian, so part Potawatomi Indian, part Irish—and in his culture, you know—and he was very, very connected to his Potawatomi roots—but in his culture, the trees were sacred, especially really old trees. And among Native American cultures, they felt trees, hundreds of years ago, a thousand years ago, were huge things, and they were holding the sky up, because that’s as far as they could see, was through the vastness of the canopy of the trees. And the tree branches in these massive trees were holding the sky up, and he just loved the idea of something living longer than him and a gift to the neighborhood. He had no interest in any kind of plaque or any kind of historic district nomination; that was not even on his radar. He was so modest, all he wanted to do is give a gift, and the gift, because his time here was quite abbreviated, and he wanted to give a gift to the neighborhood. And that was the first modest… with Scott and he working on the trees, and then asking me to give $5,000 to Greenscape, which, you know, is not a very much money today. And you know, what, about 30-35 years ago—he died in ’95—so 30 years ago, a fairly good amount of money. And so, you know, I’d like to think that he just thought it would be a beautiful gift to the neighborhood, and that was it. Because he really, he loved Riverside. Became his true home. So much of the house I’m living in has parts that he brought into it, from chandeliers that we found, or doors that he picked up here and there, things he brought back from Oklahoma when he went to visit, because my house was a wreck. It was an absolute wreck. Now it looks okay.

Archivist: You said this earlier, but we weren’t recording. Can you say about how many trees you think were planted thanks to Tony?

Richard: Well, I think as Scott was saying earlier, you planted the initial installment was, how many, with you and him?

Scott: 40. I’m gonna say 40.

Richard: 40. Okay, that’s a lot of trees. 40, okay, from Acosta to Cherry. And then there’s some trees right on the front lawn of West Riverside Elementary that were planted. There are crepe myrtles right there, too. And then with you and I, we planted…

Scott: That was a lot. 150. I mean, it was a lot.

Richard: In installments and such. And then there was 125 we gave at his funeral. So I would say…

Scott: Four or 500?

Richard: Yeah, they tend to say it’s about 500 trees, and, you know…

Scott: And all, mostly living, all living.

Richard: Yeah, and all, you know, the diversity. I can’t imagine, if you took all those trees out of neighborhood, what would this neighborhood look like? Park Street would be fairly bland. Herschel would be gone.

Scott: Hot as hell. It’d be hot, hot, hot.

Richard: You know, parts of Willowbranch Park would be bare. But also keep in mind, as an outgrowth of all this, the AIDS Memorial Project, of which I established with [Tony] and many other friends in mind, started a policy of planting trees in Willowbranch Park.

Archivist: And when did y’all start AMP?

Richard: The organization started in 2017 with the installation of three magnolia trees that we call Love Grove. Over the years, we have planted, in that park alone, with the assistance of the city, probably 75 trees.

Scott: And they look marvelous, too.

Richard: They do. They do.

Scott: I think [Tony’s] mentality definitely carries, right? I think that it was kindness. It was memorializing. I remember I was impressed by how close he was. I had forgotten that he was American Indian. He was interested in leaving something better than he found it. Maybe that was what we discussed, you know, improving the house and everything. You knew more. But he also showed me how by kindness, you could connect with people. And I had just come back, I think I had been back in town three years and was starting a business in landscape design, but I was anxious to get out and meet people. And so that opportunity got me in touch with some really cool people back with you, you know, after a break of about 20 years. But nonetheless, Susan Fisher, I got to know her. And then I got to see how people connected with that. He started something good, and it continued. So I was exposed to a lot of people in town to find out who was interested in beautification. And that carried me to different things, but that was kind of a primer for me.

Richard: Yeah, you know, at his funeral, we had a Native American shaman who did a prayer from the altar at the Church of the Good Shepherd, which is very cool. It was really a great funeral. We had an African American woman gave the poem “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening.” We had a Jewish woman who read from Scripture, and then we had Catholics and we had a Native American. It was a little bit of of everything on that day. It was really a…

Scott: Non-denominational…

Richard: It was very spiritual. And so it was a great, great funeral. You know, if you want to go out, you want to go out in a good party. And of course, it was sad that he died so young. He was like 33 or something, 33.

Scott: I think I found him to be very kind, and you don’t find that too much. Most gay guys are decent. You don’t find that in all people. But I thought he’s very kind, you know, and that kind of attracted me. And the friendship, it was brief. It was only a couple of years that I got to work with him, right?

Richard: Yeah, when I met him, he was just so, you know, so in turmoil about his Catholicism and his homosexuality, and he just could not find a happy medium there. I said, “You have to find your true self.” And he did. I mean, it was like, this is what God created in him. God did not make a mistake in making him who he was.

Scott: There was a circle of women that I forget about, like Betsy Lovett. There were a circle of women that really advanced the gay…

Richard: Louise Hardman.

Scott: Louise Hardman. They were calm. They had the ability and the finances to help in ways. And it was women. It was no men at that time, you know, because Jacksonville was still conservative; you would be fired. I remember having friends that had to put a picture of a friend who was a girl on their desk to say, “Well, that’s my fiancée.” So they would be, like, engaged for, like, five years, because if you were found out, you would be fired. And a lot of them did connect…

Richard: Evelyn Neal was another.

Scott: Evelyn Neal with beautification of trees.

Archivist: They were probably on a lot of people’s desks. They were those friends.

Richard: That’s right.

Scott: I never faked it. I just stayed busy.

Richard: I had a picture on my desk of a lady friend and I attending the Revelers’ Ball.

Scott: Oh, yeah.

Richard: You know, because I was working out in Middleburg and Clay Hill, and I think just because I was working with little kids, they thought, “A man working with kids, you must be this.” And I thought it would be a lot easier to have a picture on the table.

Scott: You know, something I think the the appreciation of what contributions the gay community has made to Riverside over time, whether it’s not even to differentiate, but you know, it was always a welcoming community, and I think those who came prospered and stayed and invested, built, or rebuilt. There were a lot of early renovations, much like you, gay men, in Riverside and Avondale because they had the means.

Richard: Well, let’s remember Richard Stewart. Richard Stewart. Avondale is as beautiful as it is because of Richard Stewart. He owned a floral shop called Richard’s, which is now the jewelry store there, and Richard’s beautiful home at the corner of, I think it’s probably Edgewood and St. John’s Avenue or Avondale and St. John’s Avenue. It’s just a big, beautiful home. Has the ballroom on the side. Richard Stewart also died from AIDS-related illness, and he was a dynamic person. Owned bars, owned Brothers, and a few other things. And he was a modest, poor kid, but he worked very hard. He was one of the founders of RAP, along with Gustafson, who was also gay. Mark Gustafson was a founder of RAP. Wayne [Wood] would remember him.

Scott: It was natural because a lot of them, a lot of us, a lot of them, a lot of us, moved here because rents were reasonable, but also, there were a variety of apartments and homes, and most people of your neighbors were friendlier, you know, not like Arlington at that time, or not like parts of San Jose and South Side at that time.

Richard: Well, right, exactly. As I was telling Shannon, “Who lives in a marginalized neighborhood, but marginalized people?” And this was a marginalized neighborhood, so you had the musicians, the hippies, the gays, the outcasts, the funkies, and the flunkies.

Scott: I remember somebody getting an apartment for $75 in Riverside. It was probably worth, like I said, less. Mine was $100, you know, the one that I had on Boone Park Avenue. It’s since been demolished.

Archivist: Can you all talk to me a little bit about what’s in this book? You mentioned the quilt? Can we get some of that recorded? Because I think he talks about some of it before…

Richard: I have a lot of pictures here of Tony, but I do have the notification about his quilt, and it starts off by saying, “I am writing to let you know that your panel you created is now formally part of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, one of the most potent tools in the global fight to end HIV and AIDS. Your panel has been bundled with seven other similar panels into a 12-by-12-foot block, and will begin the journey of inspiring hope and compassion across the country and across the world.” Quite honestly, because it’s all over the place. It travels all over, and what’s really cool about it, it’s has his birthplace and location in Oklahoma, and his death place in Jacksonville.

Archivist: So who is this from? And what’s the date?

Richard: This is from the AIDS Memorial Quilt. And the date is November 13, 2002. [Tony] had died seven years earlier in 1995. And so let me say what it looks like. It’s a tree. As I said, the main part is a tree, but at the bottom, it’s all these flowers, and each one of these flowers is made up of fabric from a friend that we asked to add to his quilt. So a friend would contribute a tie he wore at the funeral of his partner, or a shirt of a boyfriend, his first boyfriend, that he had kept forever, or a friend may have given him a part of her wedding gown, or another friend may have given her child’s booties, or something like that, little things. And so we took all of that, and my good friend, she helped sew it all together. And to look at it online—and we have a panel number, and all of that that we can access for the archives…

Archivist: So this still circulates? His panel in the quilt still circulates for exhibits?

Richard: It circulates all over the country. It’s been here in Jacksonville at least one time. So all of the flowers on the bottom have—and even for my piece of fabric that I used was the herringbone upholstery of my sports car seat. Exactly, it was getting a little tattered, so I used the herringbone fabric.

Scott: You didn’t need it for your hat, so you decided, eh, may as well give it to that.

Richard: Yeah, but it’s really cool. And then inside of it, because it’s a quilt and there’s some space, I added pictures of him being on safari in Kenya, petting an elephant or something. He was playing with an elephant in one of these pictures, and that’s added to it, as well as my speech. I gave a speech on his quilt and how he envisioned that it would be a home for birds and other living creatures.

Archivist: Oh, cool. In the Navy?

Richard: Tony Suzinski, Ron Saruga—he’s already passed away from AIDS-related illness. And Louise Hardman; she already passed away, too, but from other things.

Archivist: And this is inside your house?

Richard: Yes, it is.

Scott: I’m not sure, but I think that Louise became an ordained minister before she passed.

Richard: I wouldn’t be surprised.

Scott: I think she did.

Richard: She was really very spiritual, kind, yes.

In summation, I would say that Tony was not extraordinary in the sense that he was an average guy, but he had the intent to do something altruistic—that he realized his life was coming to a close, and he wanted to give a gift to a neighborhood. That he did not have a long history with, but he had grown to be very fond of, and he had the good fortune of knowing a friend like Scott Dowman, who was able to help articulate his vision, Greenscape, and RAP. And so to his memory, we are here, and I’m happy that I was able to execute this for him. Want to say anything in summation?

Scott: I am pleased to be included and remembered, and I want to take a walk around and see these trees. The Chinese proverb that talks about the perfect time to plant a tree is 25 years ago. We’re five years greater than that, but I think I want to stand where they are and imagine them not there. And I think that that will be eye-opening, pardon the pun, but, I mean, I think it’ll be a realization that just what value that he added by starting that. Every tree, probably hundreds of them, can be imagined not being there if he had not done this. And I don’t think anybody else would have either.

Richard: Indeed, you’re right. Walk out the front door of this one office, you see the two trees that you planted within that very first time—very first trees, the ones right across the street at the house. Yeah, I showed you a picture of [Tony], the former owner of the tree.

Scott: The owner had just had a baby. The baby is 30 years old now.

Richard: Right. And you, a city councilperson, and then the Executive Director of RAP. We’re all standing by that first tree.

Scott: You won’t recognize me. I had a lot more hair.

Richard: The RAP newsletter was about his obituary, and that was a Greenscape article.

Scott: I wondered if a follow that would be fascinating if the Times Union would take a look at 30 years ago, a site there and now, and the quick story on what did transpire as a result. Because I think people now take them for granted. They probably think, What a great neighborhood. There’s a lot of trees, trees everywhere.

Archivist: They just assume the city did it on their own or something.

Scott: It’s no problem, but people could be reminded of the importance of planting trees even today, you know, get them planted, because in 20 years, that’ll make a difference.

Archivist: Tony provided a good example of what a neighbor should be. You know, what one person can do.

Scott: Amen.

Richard: Yeah, I’ll get that article about the trees being planted again. I’ll find out. I keep all of that stuff. And I’ve got two plaques from the mayor’s environmental luncheon. I got two plaques for Tony’s Trees.

Archivist: I’m going to sign us off here. So this is Elaine Akin, RAP Archivist, signing off at 4:18pm.