by Elaine Slayton Akin, RAP Archivist

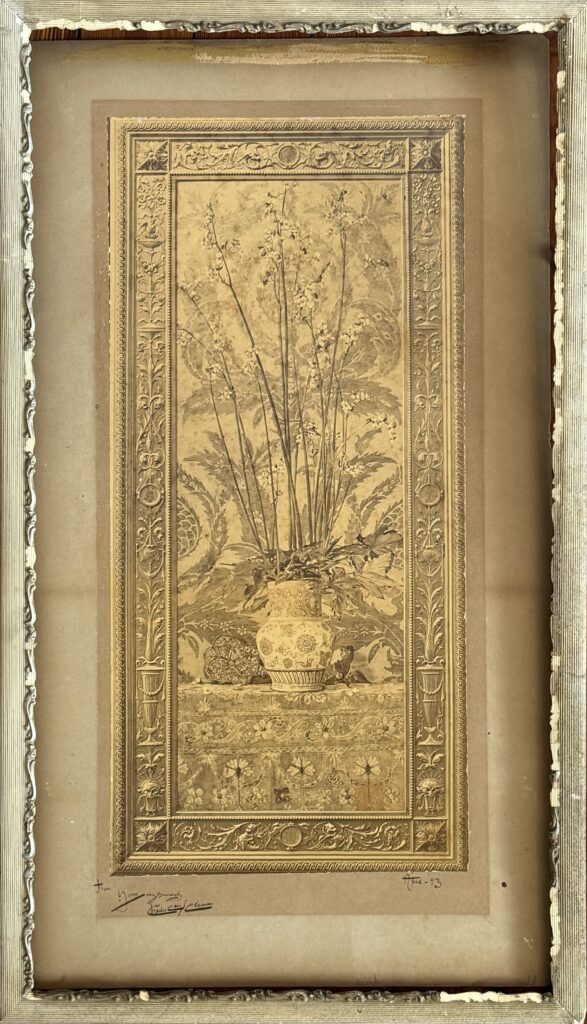

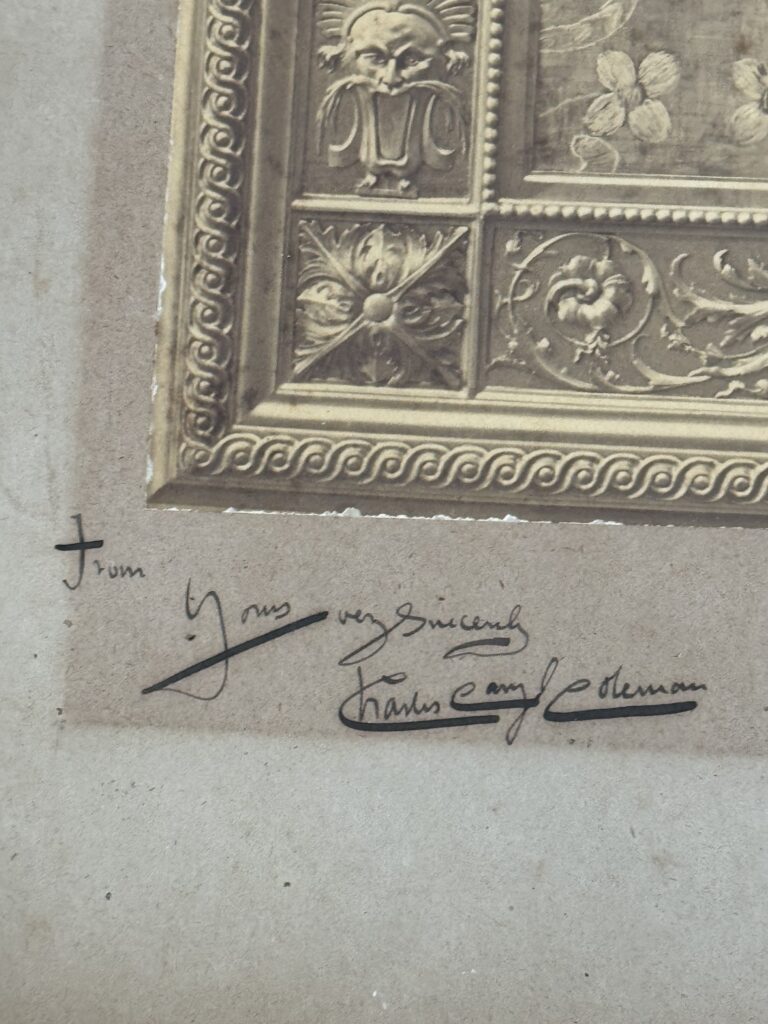

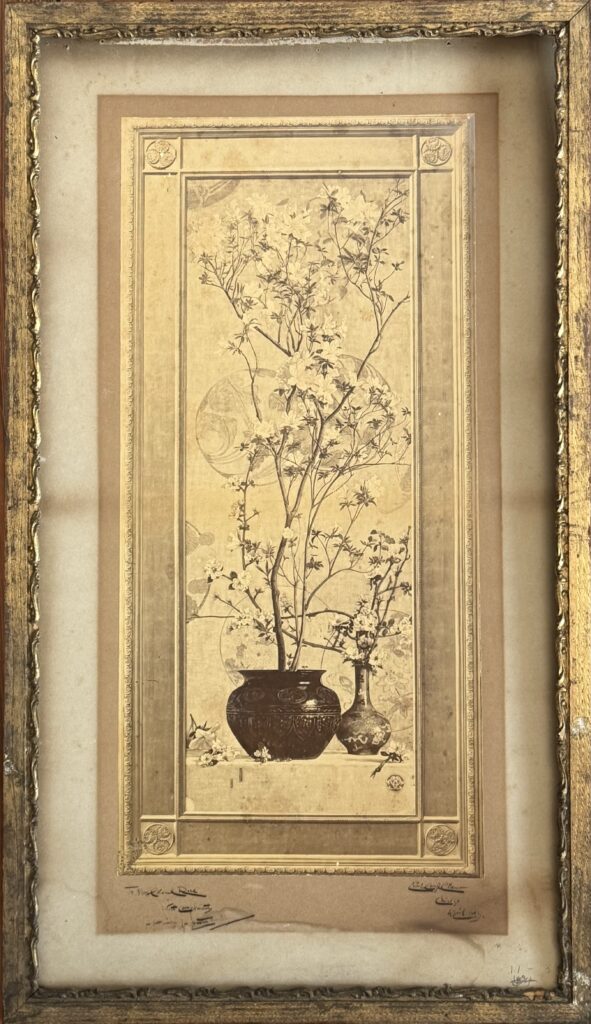

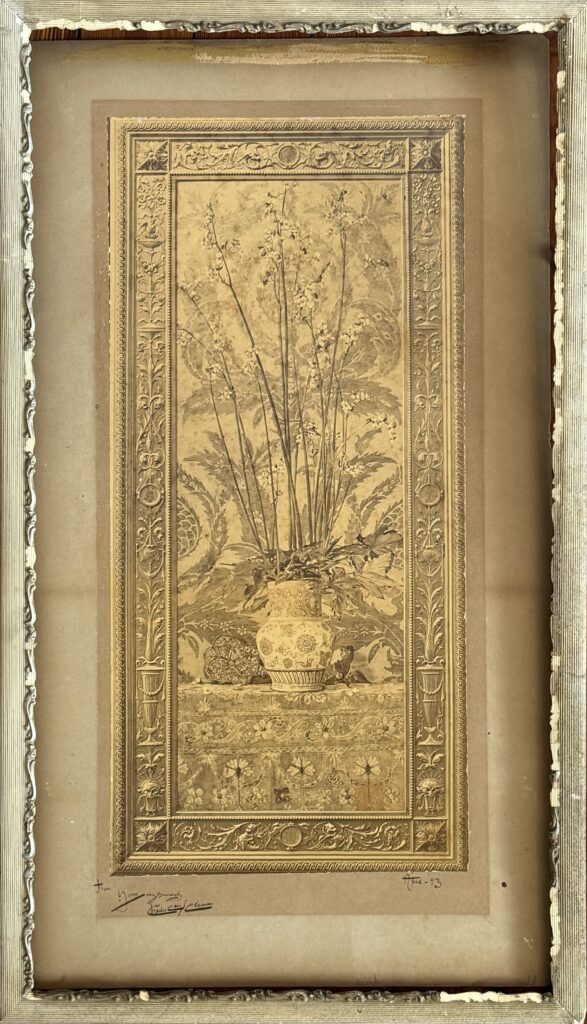

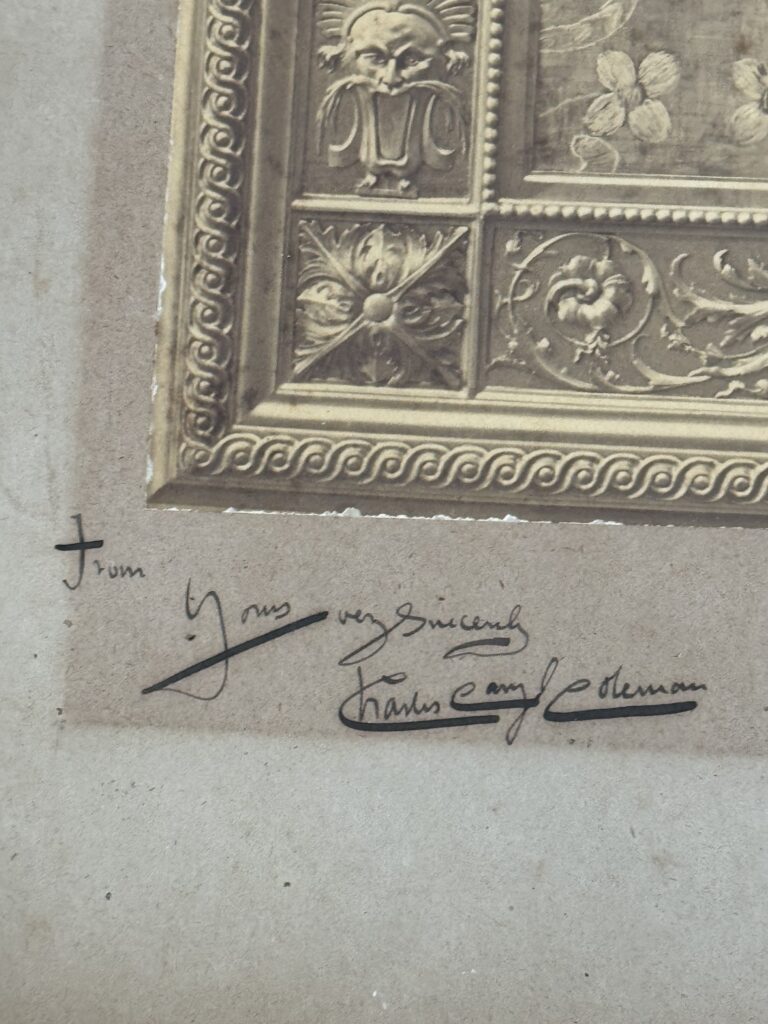

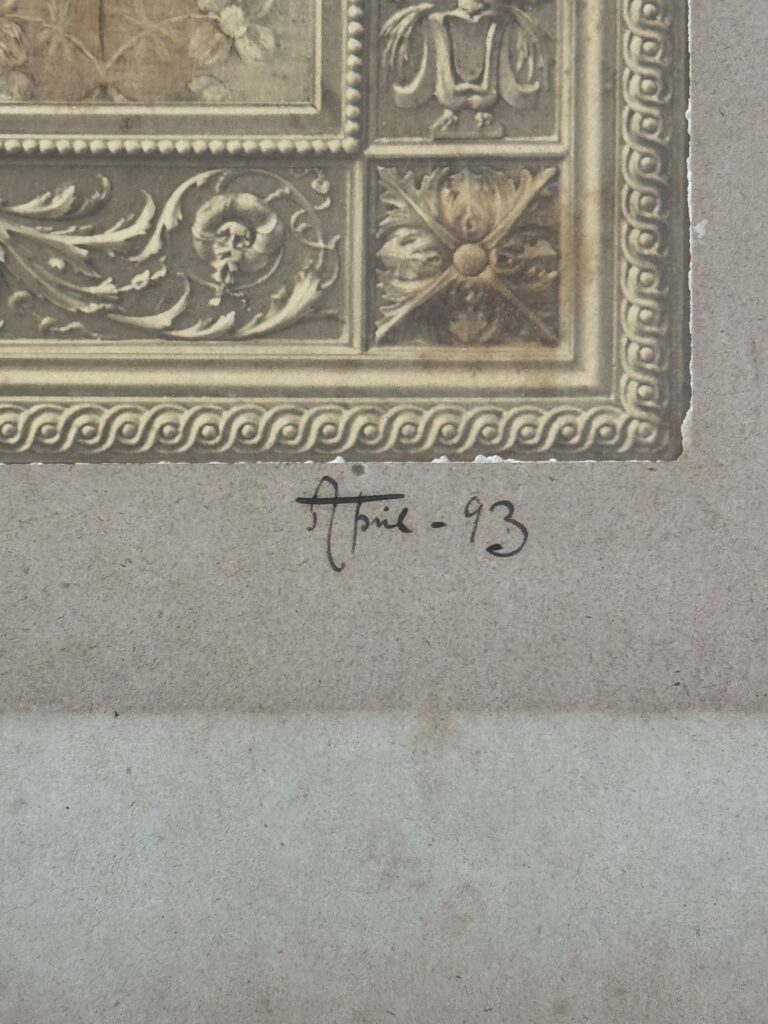

The story of these lovely sisters, or companion, prints by Charles Caryl Coleman (1840–1928) really begins with two sisters–our very own Grace Huntington Buckland (1865–1940) and her beloved sister Elizabeth “Eliza” Huntington Rice (1849–1918) of Cincinnati, Ohio. While many family records and much correspondence remain for research, we are fairly confident that after Eliza’s death in Newport, Rhode Island, many of her possessions were dispatched southward to her sister in Jacksonville. We have found several documents, photos, objects, and artworks that bear Eliza’s name as owner, including these Coleman prints hand-signed by the artist, “To Mrs. Colonel Rice with Compliments, Best Wishes for Easter Sunday, Charles Caryl Coleman, Chicago, April 1893.”

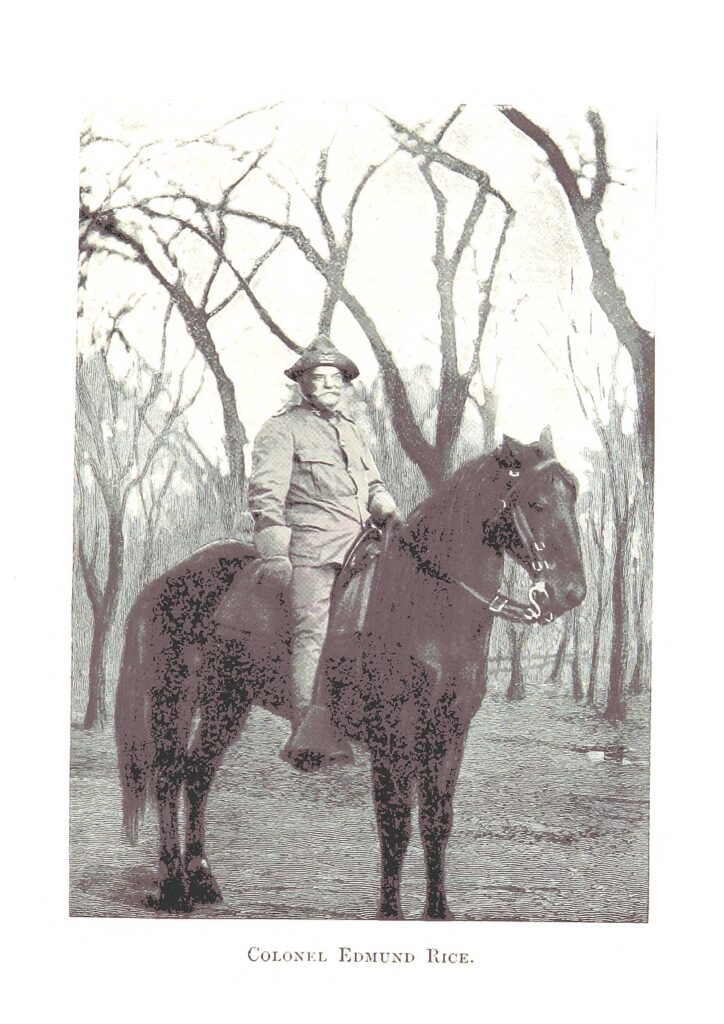

Eliza became the second wife of Colonel Edmund Rice in 1881. Rice was a highly decorated military leader, diplomat, and inventor, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient who served notably for the Union Army in the Battle of Gettysburg in the U.S. Civil War and in various international appointments under Presidents Lincoln through McKinley.

Relevant to this story, the well-connected Col. Rice also served as the Commandment of the Columbian Guard at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Sound familiar from a certain artist’s inscription?

Every element of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was built to follow the Beaux-Arts principles of design, and many artists, designers, and influencers of the time who fit the bill were recruited to contribute their unique gifts to the epic soirée. According to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, one Charles Caryl Coleman painted a mural for the Fair and is known to have produced photographic prints of the mural. We believe with confidence these prints are precisely the prints in possession of the Buckland House today, as Chicago was the point of acquaintance for Mrs. Col. Rice and Coleman.

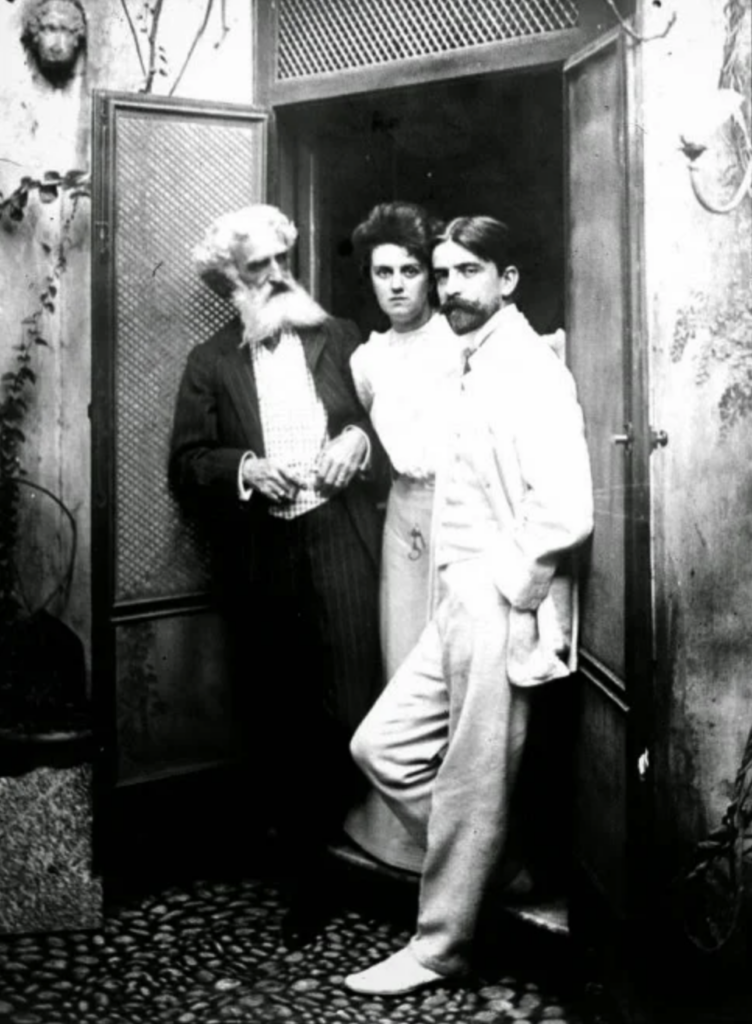

Coleman was a native of Buffalo, New York, and began his early artistic training as the nephew of an auctioneer and gallery owner and the student of painter William H. Beard. He moved to Paris in 1856 and studied more seriously under Thomas Couture, also befriending fellow artist and future lifelong collaborator Elihu Vedder (whose work is also in the Buckland House collection with a handwritten inscription to Eliza, but that’s a story for another blog post!). Coleman returned to the U.S. for a brief time, serving in the Union Army during the Civil War then setting up studio and exhibiting in and around New York.

The progressive allure of Europe called, however, and Coleman returned overseas in 1867. He joined a vibrant, international community of artists, including Vedder, in Italy where over time he mastered the hallmarks of the International Aesthetic Movement, known today as a somewhat fluid visual art category that combines elements from Medieval, Renaissance, and Neoclassical periods and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, among other influences.

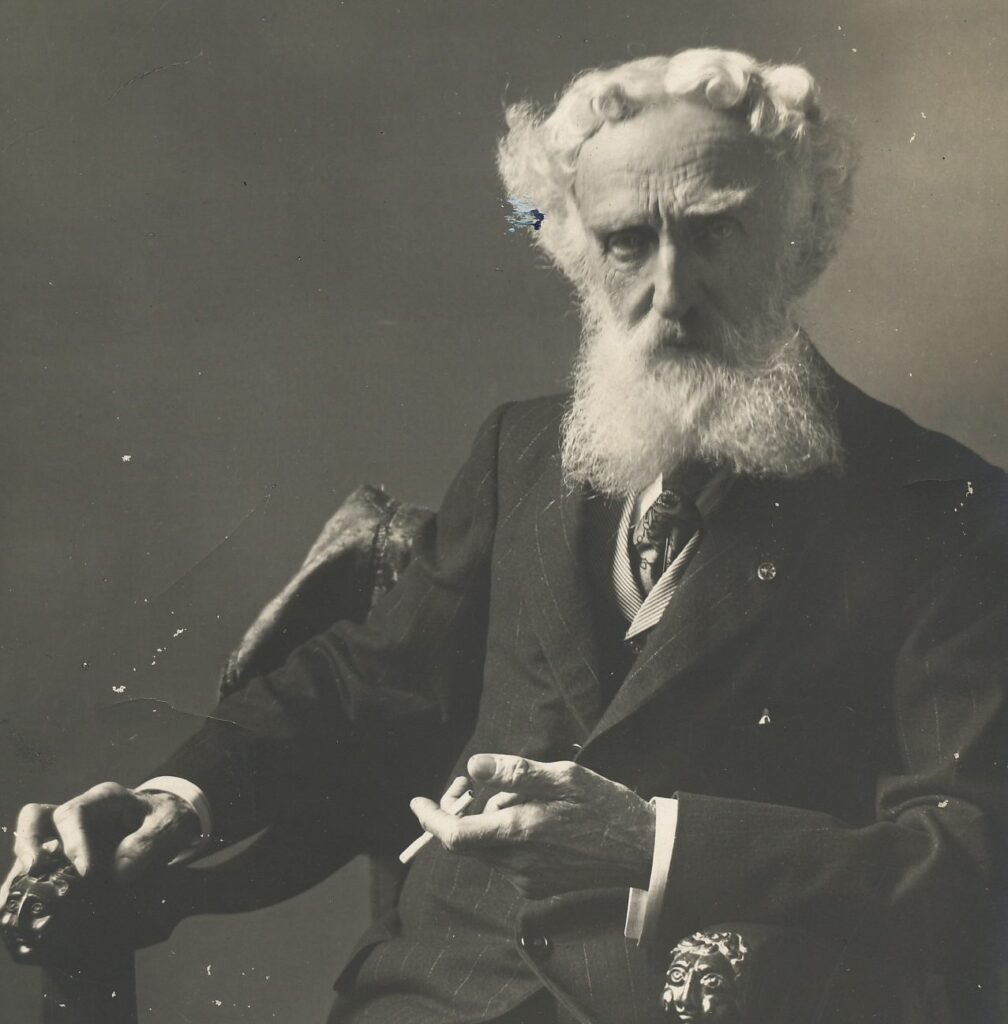

In 1886, Coleman bought the famed Villa Narcissus on the island of Capri, where he lived for the rest of his life, but maintaining strong ties to the U.S. and his American patrons. His scenic, lush surroundings naturally influenced his style, and he incorporated many classical elements and motifs in both his paintings and hand-crafted frames that deemed his work as superior in “decorative elegance” (biographical source: Smithsonian Archives of American Art).

Of course, it makes sense for the Smithsonian as a Coleman subject expert to include several of the artist’s works in its holdings.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York also has a couple of Coleman originals in their permanent collection (not to mention some decorative objects whose provenance once included Coleman as an owner, oddly enough), and the Met also featured Coleman in its 2017 exhibition and eponymously named catalogue In Pursuit of Beauty: 30 Years of Collecting the American Aesthetic Movement.

While the Buckland botanicals are prints of originals, most of the original panels are now located in major public collections, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (as noted above), the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Speed Art Museum, and the de Young Museum. The Smithsonian houses a large collection of photographic prints of originals, like ours, from a 2018 donation of more than 75 black-and-white photographs that were abandoned inside the eaves of an attic of a New York house, walled off with sheetrock.

Coleman is not a household name in the modern era, but his decorative flower panels, created primarily in the 1870s and ’80s, did receive some acclaim in their time. As they are described by the Smithsonian, his decorative flower panels are without question the category within which the Buckland “sisters” fall in Coleman’s oeuvre:

“Unique in the history of American art, they are rivaled in their scope and dramatic intensity only by the stained-glass panels of John La Farge. Often measuring over six feet in height or width, they feature impossibly attenuated branches of flowering fruit blossoms emerging from colorful maiolica vases or Chinese lacquer pots. These vase-and-flower arrangements rest on elegantly patterned Ottoman textiles or Indian patkas.”

Like those in the Smithsonian collection, the Buckland prints are black and white, browned with time, and individually glued down to fragile pieces of cardboard. Their wooden custom-built original frames in which we discovered them are affectionately carved with immense detail and awash with hints of metallic paint, probably handmade by Coleman. His handwritten notes in the margins, quoted above, add an endearing touch that opens a window into his personal style of communication, confirming the warm and generous person described in known accounts, especially as a leader and local fixture in Capri.

While it’s currently unknown if Grace (pictured right), and later Mary and Charlotte, inherited Eliza’s appreciation for the Aesthetic Movement, they certainly inherited her artworks and strong feminine presence for promoting the fine arts and culture as administrators of the French Primary School; art, music, and theatre enthusiasts, and avid antiquarians. Since Grace was Eliza’s assumed beneficiary, we have every reason to believe the sisters were close, as was Eliza’s relationship with her nieces Mary and Charlotte. Mary fondly mentions receiving a package from “Aunt E” in a 1915 journal, and we have glimpsed many other genial references to Eliza in Buckland records, although they need further research as time allows.

Much like the Commemorative Enamel “Cup of Sorrows” from the Coronation of Tsar Nicolas II of Russia (1896) featured in our last blog highlight, the Coleman prints have inadvertently become another thread in the historical backdrop of the Riverside Avondale neighborhood. Although they were not created here nor created by an artist from here, they have been living right here in the Buckland House at 2623 Herschel Street since the 1920s without our possible fathom of how many viewers have been inspired by them before they were likely stored at Charlotte’s death in 1990. From Buffalo to Capri and Chicago to Newport then Jacksonville, these unique prints represent the people of our community in many ways–a melting pot of all kinds with an even stronger impact in a reframed context. After a brief restoration, we are delighted to be able to put them back on the Buckland House wall, where they belong, to continue their life stories–and factor into your life stories–very soon.