by Elaine Slayton Akin, RAP Archivist

From its grass-roots beginnings in 1974, Riverside Avondale Preservation (RAP) has focused its resources on protecting the history and culture of the Riverside and Avondale historic districts, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 and ’89, respectively. RAP has long-championed the beloved character of the neighborhoods, for example, through the Historic Preservation Ordinance of 1990, establishing the Jacksonville Historic Preservation Commission. As much of our readership already knows, RAP is located in the historic Buckland House, constructed in 1912.

Its first inhabitants were Ohio transplants George, his wife Grace, and their daughters Mary (age 16) and Charlotte Buckland (age 7), the latter of whom lived in the home until her death in 1990. At that time, a distant Ohio cousin bequeathed the Buckland House and its contents as the new headquarters of RAP. Deeply rooted in our predecessors’ legacies, RAP works to enhance and preserve the unique quality of life of Riverside Avondale residents, yesterday and today.

Charlotte and George Buckland, 2623 Herschel Street, Jacksonville, 1912.

But “can you love the past without being held captive to nostalgia” (Monstrous Beauty, 2025)? In 2024, RAP was able to shift its priorities to also include the preservation of the long-accumulated archival materials and decorative arts collection in its possession originating from the Buckland family, donations from Riverside and Avondale residents, and RAP’s organizational files. As present-day archivists, my colleagues and I working at the intersection of material culture and history must be more aware than ever of cultural appropriation, historical inaccuracies,

and the European supremacy veil and how to accurately document the items in our collections free from the biased lens these human constructs overlay. At the Buckland House, I’ve had the opportunity to explore contemporary archival challenges in a variety of directions, but the Bucklands’ noteworthy collection of archival and decorative arts materials produced in or inspired by East Asia, primarily China and Japan, has proven a rich and complex case study for research.

Saucer with Floral Motif, Limoges, France, c. 1900.

Some imagery to follow may contain sensitive content that could be triggering for some viewers. It was created during a time before education on cultural appropriation became widely disseminated, and it may be challenging to engage within the context of today.

For Example: Blonde Child in Kimono

Hand-painted platinotype by Reinhard Grob, Fremont, Ohio, c. 1900, Buckland Collection.I recently visited the exhibition Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The introductory wall text read: “Chinoiserie, the effeminate, ornate style fed by a demand for foreign luxuries and fantasies of an imaginary Far East, filled countless homes across Europe and… America.” The Bucklands’ was one of those homes. One of my greatest responsibilities in this case is determining how to respectfully describe and display material culture originating from the problematic “Oriental” movements of Chinoiserie and Japonisme in the archives of the Buckland family dating as far back as the late 19th century.

While this seemingly peculiar collecting hobby offers an intimate portrait of one family’s interests, it more importantly reflects the same world perspective of upper-class families across early 20th-century America whose generational wealth largely determined the trajectory of American civilization and the positioning of “the other.” Despite early Americans’ intent, or the lack thereof, to cause harm to the people of color living in their own cities, the prevailing lack of education available regarding non-Western heritage precipitated misconceptions and inaccuracies for centuries to come.

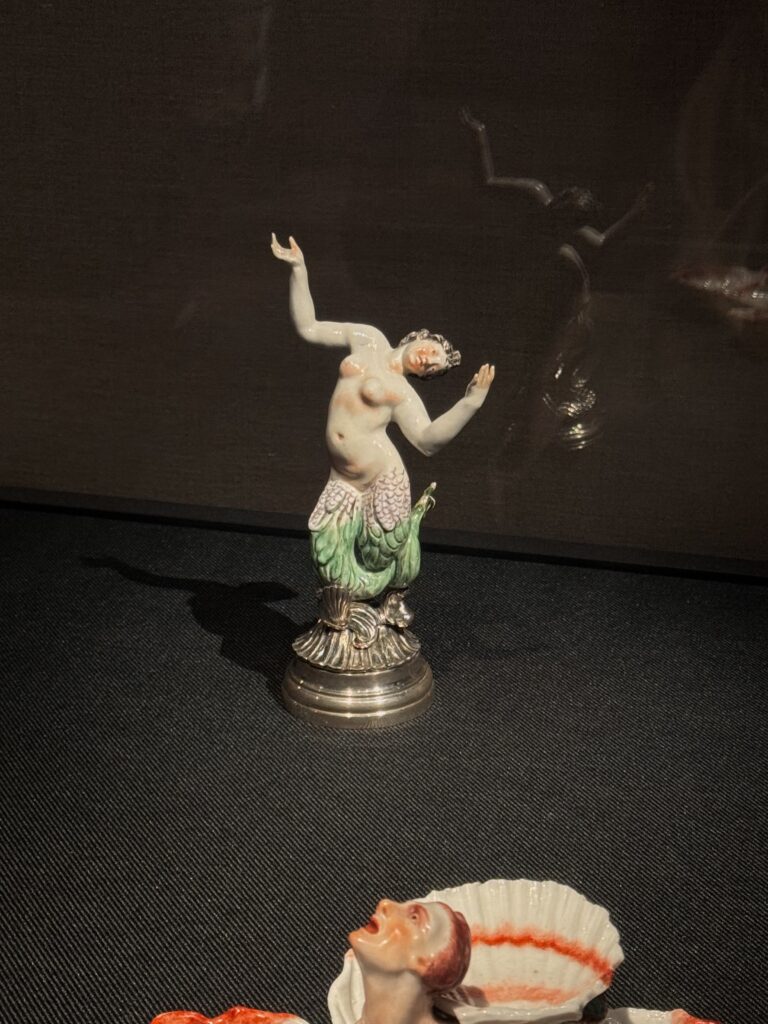

Mermaid, Doccia Porcelain Manufactory, Italy, c. 1750-55 in Monstrous

Beauty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May 2025.

The degree to which American tastemakers have historically appropriated and collected non-Western decorative arts, material culture, and design is, naturally, as profound as the rate by which said materials are entering American museums, archives, libraries, and other institutions today. While the charge of “wokeness” pervades our collective conscience and holds individuals accountable through social currency, the arts and culture world is still lacking firm consensus on the responsible treatment of sensitive materials. Even the goliath Smithsonian (Masum Momaya, 2017) and National Archives (Brian Boucher for ArtNet, 2024) are evidenced offenders of white-washing unsavory American imperialism.

Demonstrating the inimitable value of collaboration for the archivist, my research on the Buckland collection has been guided by one of Masum Momaya’s 10 principles “for an anti-racist, anti-Orientalist, activist approach to collections”: “to establish opportunities for community engagement, co-construction of meaning, and destabilizing the notion of authority residing in one party” (2017).

Left to right: Hand-painted Porcelain Teacup with Landscape Motif, Japan, c. 1900, artist once known; Detail, 7-Drawer Wooden “Chinese Apothecary”-Style Cabinet, c. 1900, artist once known; Teacups with Floral Motif, set of five, China, c. 1900, artist once known.

Accordingly, I have consulted traditional and nontraditional partners alike, from fellow archivists, librarians, curators, and historians to artists, interior designers, university professors, and AAPI activists, all of whom enhance meaning in a more holistic way. Their contributions have informed almost every aspect of what you’ll read here. The issues of outdated interpretations and neglected provenances could prohibit the responsible treatment of sensitive materials in our repositories. Together, however, we can honor the whole histories of the records and objects we steward and transform their miseducation into reparations, accessibility, community outreach, and widespread unity.

The Bucklands

My research is a work in progress, and its outcomes, many of which are actively being formed as new perspectives are gleaned, would still be useful but less substantive without backstory. George Buckland married Grace Huntington in Fremont, Ohio, in 1891. After the birth of their daughters, they landed in Jacksonville in 1910, where George worked for the Jacksonville Gas Company.

He also wrote a weekly column, “Family Pages from the Past,” for the Florida Metropolis newspaper, in which he would chart the history and significance of antique objects from members of the community. One column in 1916 even featured a filigree ivory “bridal fan,” carved by Jean Pillement of Paris in 1764, his work “distinguished from other men of his profession by… ‘chinoiserie.’” Meanwhile, Grace and Mary operated the French Primary School from 1918 into the 1940s from the first floor of their home. Charlotte studied botany at Agnes Scott College, and later returned home to teach at the Julia Landon College Prep School.

Detail, “Family Pages from the Past” column by George

Buckland; The Florida Metropolis, November 4, 1916.

The Bucklands also enjoyed the benefits of numerous affluent connections. George was the son of Charlotte Boughton and Civil War General Ralph Pomeroy Buckland—law partner of the future President Rutherford B. Hayes. George matriculated at the Cincinnati Law School with Charles Dawes who would become a lifelong friend and the Vice-President of the United States under Calvin Coolidge. As for Grace, her sister Eliza married Brigadier General Edmund Rice in 1881, appointed by President McKinley as a senior colonel in the Philippines. The couple was afforded exposure to foreign cultures that trickled down to the Bucklands in the form of inherited souvenirs, now at RAP. Between George’s affinity for rare and storied objects and the gifts bestowed by friends in high places, it’s hard to know now the provenance of everything the Bucklands owned, but one truth rings clear: the materials originating from Asia or Asian design are a small yet distinctive subset of the Buckland collection that requires special attention.

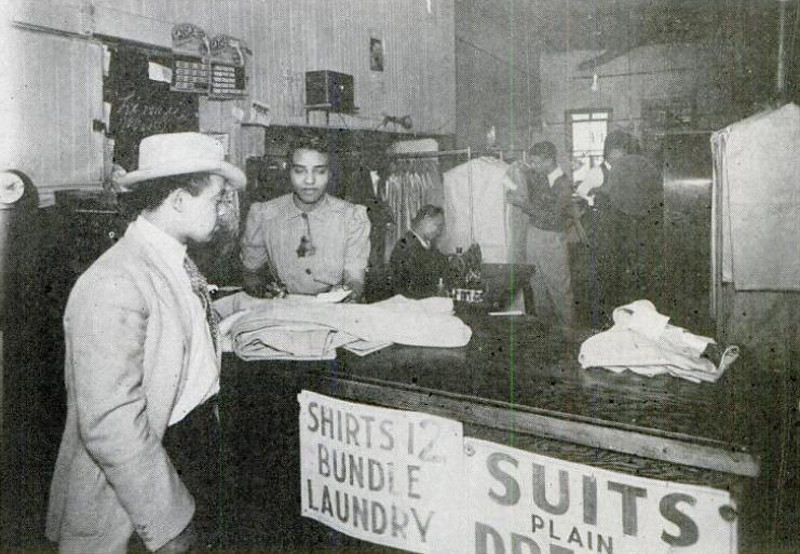

Left to right: Inside Broad Street Cleaners, part of Black Jacksonville’s premier business district during segregation, courtesy The Crisis Magazine; Chinatown, New York, by Arnold Genthe, courtesy Library of Congress, c. 1900.

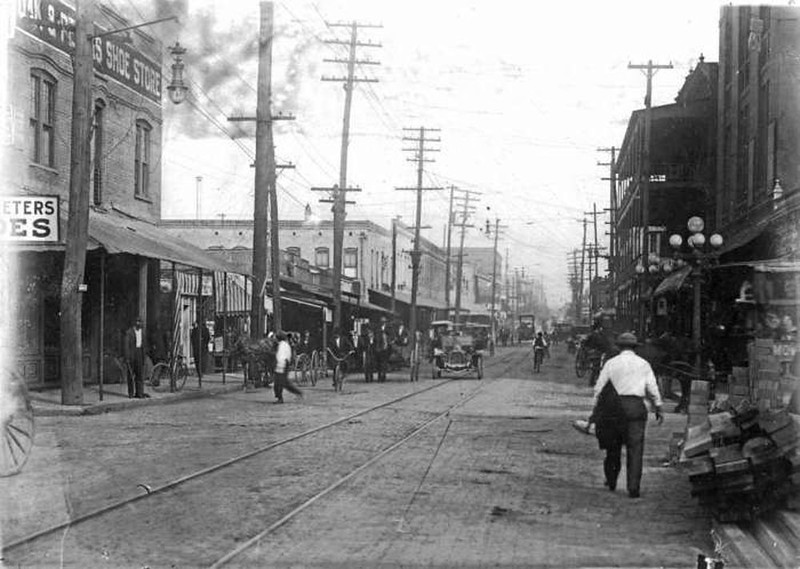

Broad and Houston Streets (site of many Chinese and Black-owned laundries), LaVilla, 1915, courtesy Jacksonville History Center.

Early 20th-Century Jacksonville’s Urban Core

The Jacksonville of the Bucklands’ era was recovering from the Great Fire of 1901. Metropolitan reconstruction and expansion southward along the St. Johns River were in full swing by the 1910s, although segregation between the urban core and the adjacent suburbs persisted. After the Civil War, “some white Floridians turned enthusiastically toward imported Chinese workers as a panacea for the state’s [agricultural] labor needs,” according to Raymond Mohl in Far East, Down South: Asians in the American South (2016). Despite the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the African-American community LaVilla had become home to an emerging Chinese population who famously operated 25-plus commercial laundries from about 1900 to 1960 (The Jaxson, 2022), although finding photos of Chinese Americans from that time period is even more unlikely than those of African Americans, Mai-Lee Chai disappointingly notes in “The Missing Images of Chinese Immigrants” (The Paris Review, 2018). A 1904 article in the Jacksonville Metropolis records “The Laundry Predicament”:

The arrest of several Chinese men under the Exclusion Act that upset patrons whose clothes were trapped inside the closed laundries. The dichotomy between a Chinese-American’s lived experience and the Westerner’s imagined utopia of mainland China would grow wider as American imperialism catalyzed suspicion of immigrants with terms such as “Celestial” and “Oriental” yet plagiarized their profitable qualities, including Chinese design on planters, ginger jars, and porcelain acquired by the wealthy class.

Detail, “The Laundry Predicament,” The Florida Metropolis, March 25, 1904.

Members of the Garden Club of Jacksonville, by Woodward, c. 1920, courtesy Garden Club of Jacksonville.

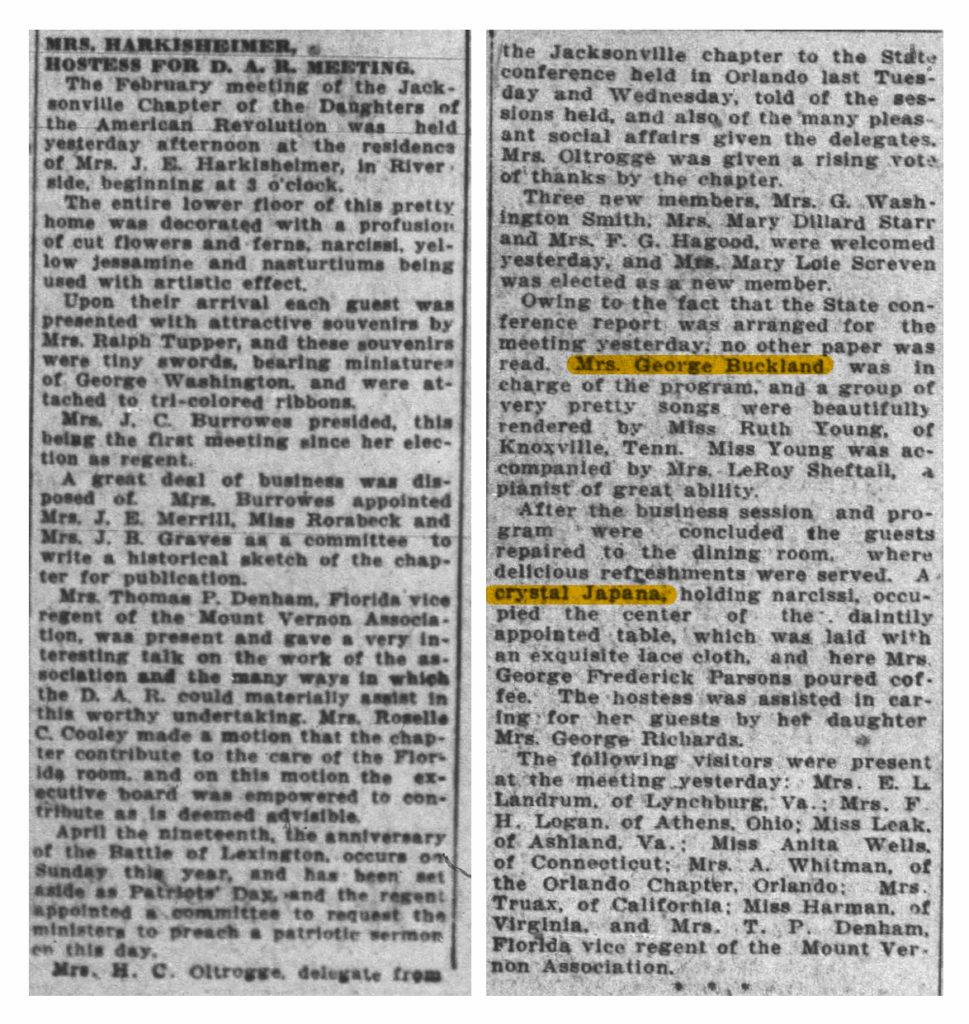

Another Metropolis article from 1914 records the occasion of a DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) meeting, in which a “Mrs. George Buckland” so happened to be involved, where “crystal Japana”—presumably a type of vase in an appropriated Japanese style—holding narcissus flowers were used as centerpieces. And Jaxsons got an especially immersive East Asian

Detail, “Mrs. Harkisheimer, Hostess for D.A.R. Meeting,” The Florida Metropolis, February 12, 1914.

experience with the “Oriental Gardens” just south of San Jose Boulevard and Hendricks Avenue, operated by businessman George Clark from 1937 to 1954. The gardens were wildly popular, appearing on postcards and in the backgrounds of countless family photos.

“The Oriental Gardens” postcard, courtesy Florida State Historical Archives, postmarked 1948.

Trade Routes, Missionaries, and Cross-Cultural Influence

Globally, America’s reasons for opening trade routes with China in 1784, and later Japan in 1853, are vast and too dense for this post, but Americans’ fascination with East Asian porcelain and lacquerware and the perceived gentle, bucolic lifestyles they portrayed is among the top. Ironically, John Murray Forbes, a wealthy Boston railroad pioneer, bought and platted 500 acres along the St. Johns River in 1868—now the Riverside historic district.

Detail of East Asia, Catalan Atlas, Majorcan Cartographic School, c. 1375, courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

As a young adult, he worked as a supercargo in Canton, returning to Boston in 1837 with a small fortune from Cantonese tradesman Hou Qua to invest in a fleet of clipper ships and furthering the trade routes to the Far East. Traveling the world, even for the wealthy, was uncommon before the 20th century, so Americans at home relied on their intrepid acquaintances to taste-make. Over time, original imports lost their contexts and evolved into derivative, European-made knockoffs, demonstrated by the evolution of this Japanese octagonal dish:

Octagonal Dish left to right: Japan, c. 1700; Meissen, c. 1730; England, c. 1755; courtesy Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain by Stacey Sloboda (2014), page 23.

Original decorative objects and textiles from China and Japan featured traditional motifs symbolizing the values, religious beliefs, and imperial dynasties of each culture, often through the elegance of natural elements, like animals and the environment. This authentic symbolism was appropriated into superficial pagodas, kind climates, and lithe bodies, American appetites whetted by, among others, Christian missionaries like Pearl Buck, author of

Pearl Buck, portrait by Clara Sipprell, c. 1950, courtesy Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

The Good Earth (1931), “[propagating] rosy depictions of ordinary Chinese peasants” in need of civilizing that would influence millions of her contemporaries and their descendants. In The Hamiltonian, Suzette Cain paints a full picture: “The China described by missionaries easily took hold in Americans’ imaginations because few Americans had any other knowledge of China. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act exacerbated the gap in Americans’ knowledge, as American historian James Bradley has summarized: ‘The cleansing of the Chinese from America’s West [after the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act] created a vacuum in U.S.-Chinese affairs, as few Americans would ever encounter a Chinese person again'” (2023).

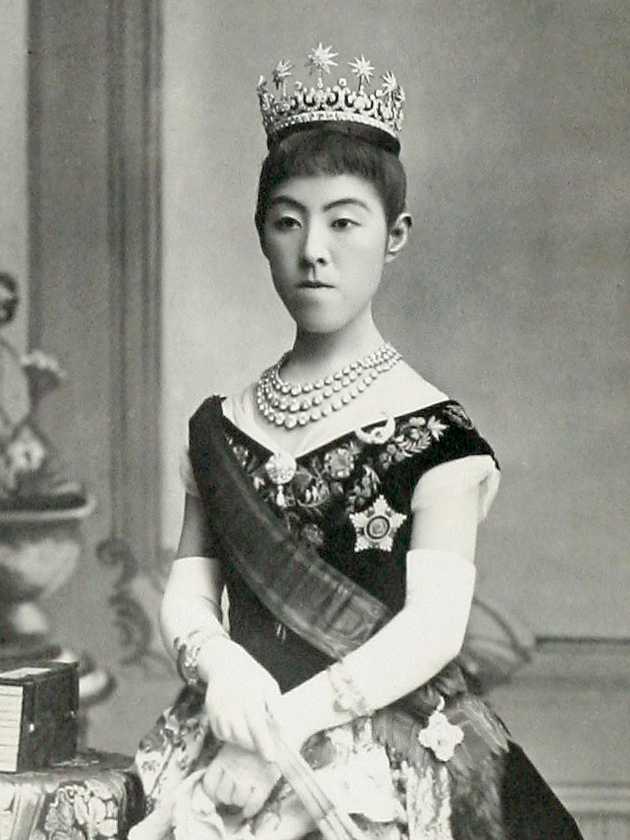

Interestingly, the presence of Westerners such as Buck living in Far East countries in part propelled a cross-cultural exchange that necessitates mention; the borrowing of cultural identities occurred both ways in some cases, although it’s difficult to qualify consent in the throes of East and West power dynamics. The Empress Dowager Shōken (1849—1914) of Japan requested an official portrait in Western dress, for instance, and the first graduating class of University Medical School, Canton, were photographed in Western suits in 1911.

Empress Dowager Shōken in Western Clothes, photographer once known,

1890, courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art.

Left to right: Susie C. Rijnhart, photographer once known, c. 1900, courtesy With the Tibetans in Tent and Temple by Rijnhart (1901), page 313; First Graduating Class of University Medical School, Canton, by Josiah McCracken, 1911, courtesy University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

Another Western missionary, Canadian Susanna Carson Rijnhart (1868—1908) was a doctor and founder of the Disciples of Christ Mission to Tibet who is well-known to have, upon arrival, adopted the native dress for the rest of her life. From 1900 to 1925, Protestant medical missionaries comprised a considerable population of Westerners visiting the East—the “Golden Age” for Christian missionaries in China, setting the stage for a dichotomous view of China, Japan, and other Asian countries. As Chinoiserie design raged in popular culture, letters and photographs poured into the United States from white, evangelizing Christian Americans deployed to “save” suffering peoples with “first-world” advancements and baptismal waters. Interior designer Young Huh explains, “It’s one thing to admire from afar and purchase products as equals—such as buying an Hermès bag and revering it. It’s another thing if you are in a position of power looking down at the cultures that you’re replicating.”

Chinoiserie, Japonisme, and Cultural Appropriation

The French term chinoiserie, meaning “Chinese-esque,” first appeared in print in Honoré de Balzac’s novel L’Interdiction in 1836, although Westerners were fascinated by the luxury goods and secondhand stories from “exotic” East Asia since the 16th century. In his 1978 manifesto Orientalism, Edward Said observes that “the West creates representations of the East because it assumes the East is unable to present or represent itself. In the process, the ‘Oriental’ subject loses its original value and meaning while being assigned new and perhaps incongruent ones by an outsider.” Consequently, culturally-diluted imitations have exalted fashion and capitalism over authentic appreciation of the people from which the non-Western objects were appropriated. Chinoiserie and Japonisme, the latter term first used in 1872 by French art critic and collector Philippe Burty, peaked in the 1920s, for one, because of their similarities in intricate detail, geometry, and color to the Art Deco movement—a trend to which we know the Bucklands fondly took.

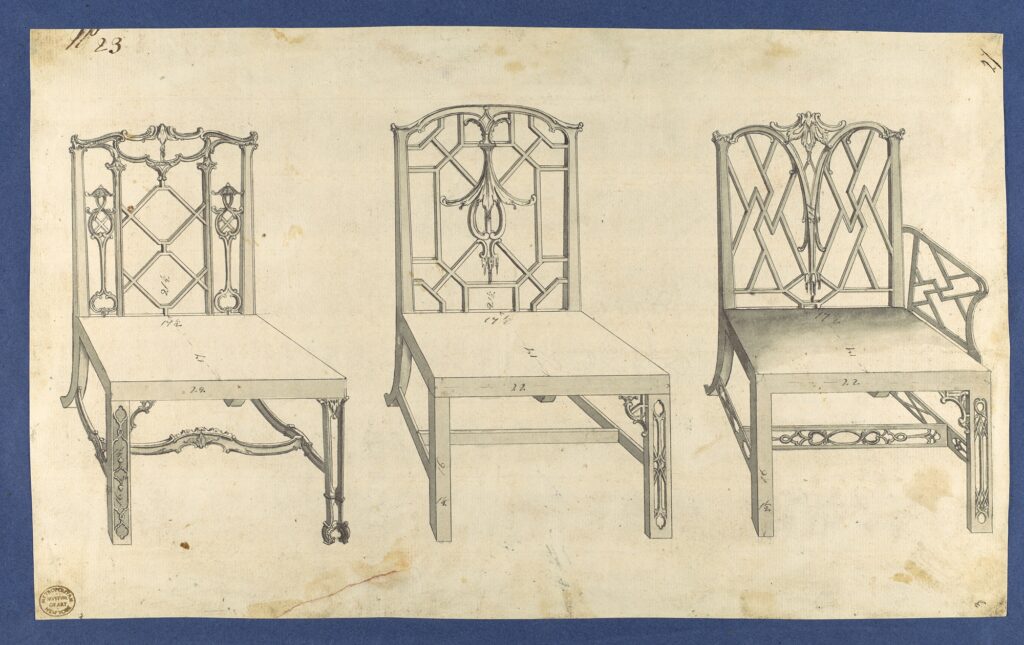

Left to right: View of the Wilderness at Kew, by William Marlow, England, 1763, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art; Chinese Chairs, Thomas Chippendale, England, 1763, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Famous examples of Chinoiserie and Japonisme the Bucklands may have seen or known include the Birds of America by illustrator and ornithologist John James Audubon; ceramic Staffordshire dog figurines; the Peacock Room by Whistler, now in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art; Chippendale furniture; and Kew’s Pagoda in London, completed in 1762 by architect Sir William Chambers. In the 2021 article “It’s Time to Rethink Chinoiserie,” Dr. Iris Moon, Associate Curator of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Met, posits, “Chinoiserie is hardly benign. It’s an incredibly destructive…way of looking at the other.” She finds the 1755 Chinese Musicians “‘beautiful’ in its craft, and yet downright disturbing, with slant-eyed figures placed in a subservient decorative arrangement.” And a couple of really great examples of the two styles are right next door to us at the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens—Gustave Léonard de Jonghe’s The Japanese Fan (c. 1865) and an entire gallery of Meissen pottery.

Left to right: Audubon’s Birds of America (c. 1827) in the Chinese Drawing Room at Temple Newsam House, courtesy Leeds Museums and Art Galleries; Pair of Chinese Dogs of Foo, Staffordshire, England, c. 1750, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Chinese Musicians, Factory Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, England, c.1755, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The RAP Collection

The following items in RAP’s Buckland archives are highlighted because they demonstrate a keenness for Chinese or Japanese design, and they were all shared with community partners in person or via email for feedback in order to fulfill Momaya’s principle for an anti-racist, anti-Orientalist, activist approach to collections. This hand-colored photograph of a blonde child in kimono is signed by Reinhard Grob, a photographer prolific in the late 19th century in George’s hometown of Fremont. The Buckland girls were not blonde, so we presume it portrays a relative or friend.

Hand-Colored Photograph of Blonde Child in Kimono, by R. Grob, late 19th century, Fremont, Ohio.

Companion botanical prints by International Aesthetic Movement artist Charles Caryl Coleman, whose work is also in the permanent collections of the Met, the Legion of Honor Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco, and the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, feature a collage of cultures. Blending China’s apple blossom, associated with love and marriage, luxurious silks, and the echo of the chinoiserie planters we see above in the early Garden Club photo with Japan’s tradition of flower arrangement known as ikebana, they are signed “to Mrs. Colonel Rice with Compliments, Best Wishes for Easter Sunday, Charles Caryl Coleman, Chicago, April 1893”—an inheritance from Eliza’s trip to the World’s Fair that year.

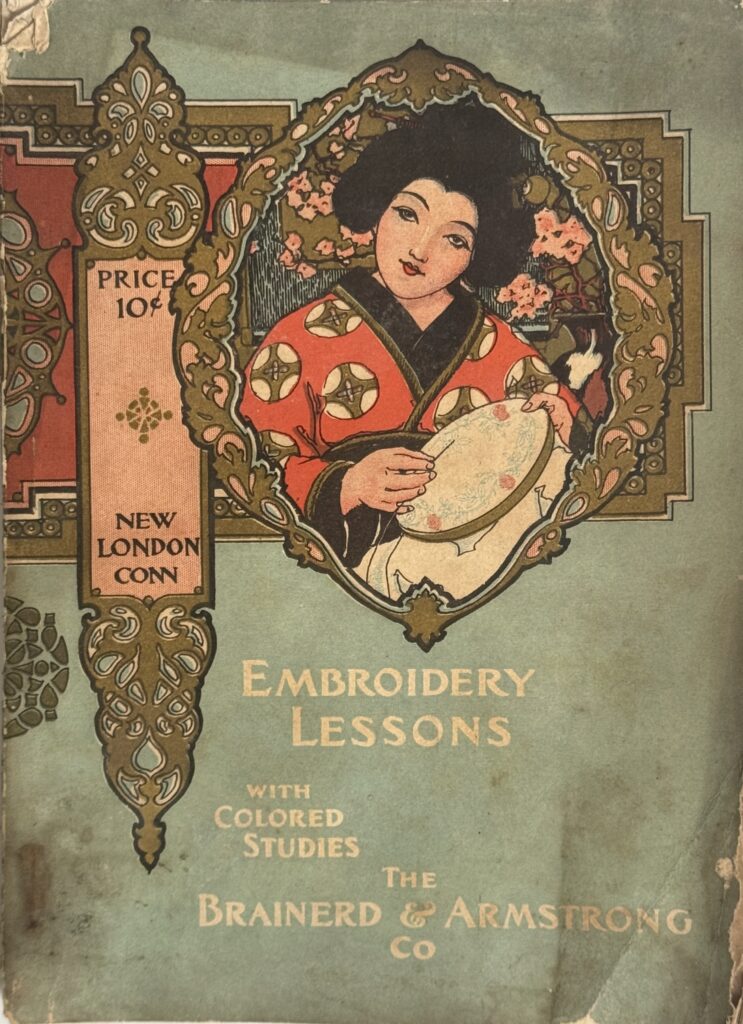

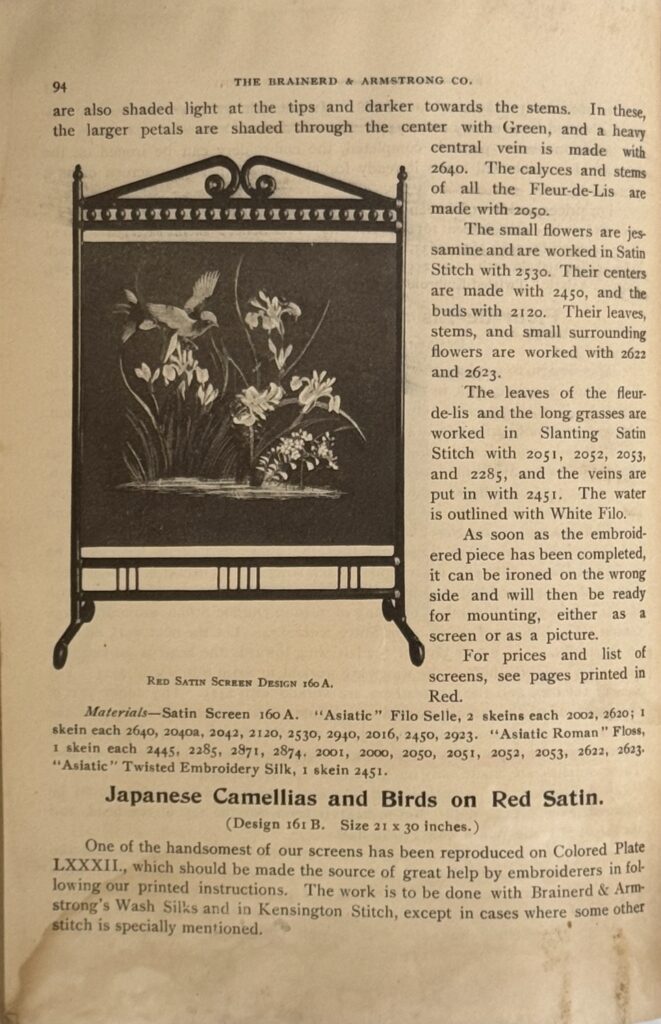

This sweet illustrated book—How to Tell the Birds from the Flowers—could have been a child’s first exposure to the art of woodcutting, rooted in both Chinese and Japanese cultures. Embroidery Lessons with Color Studies likely nods to one of the Buckland women’s leisurely activities and displays a highly Westernized version of a Japanese woman with inelegant decorative elements on the cover. Inside, instructions for stitching designs, such as “Japanese Camellias and Birds on Red Satin” and “Tinted Japanese Girl on Light Tan Ticking” guide the ever-trendy reader.

Left to right: How to Tell the Birds from the Flowers and Other Wood-Cuts by Robert Williams Wood (1917); Embroidery Lessons with Colored Studies, The Brainerd & Armstrong Co. (1901) cover and page 94.

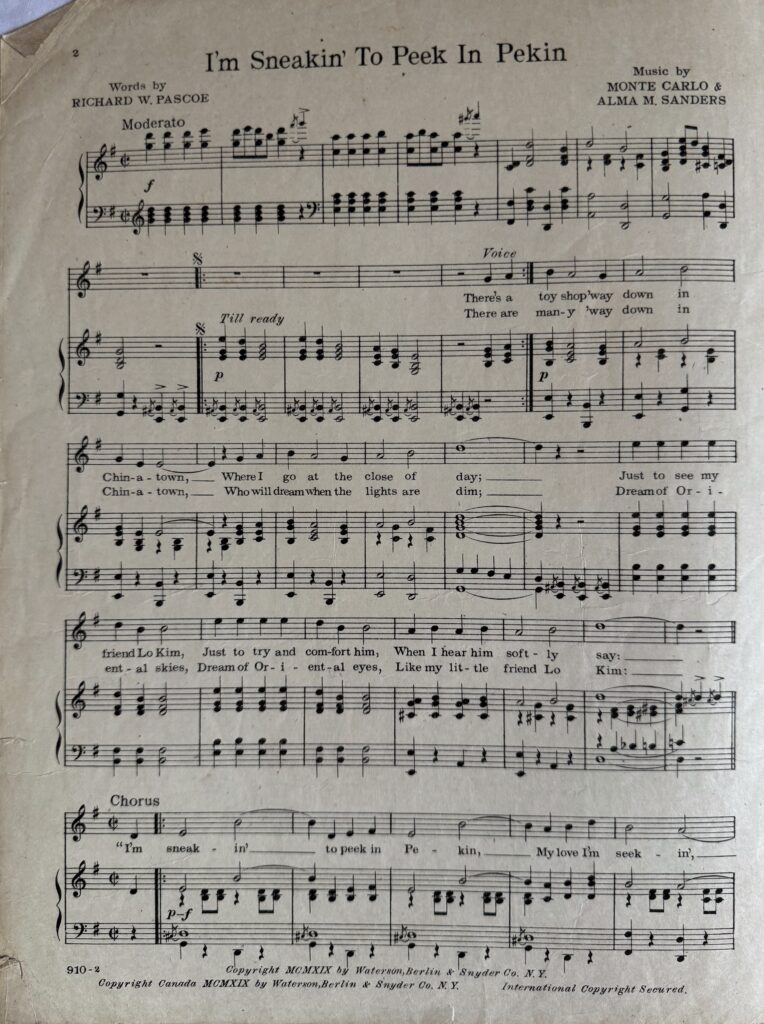

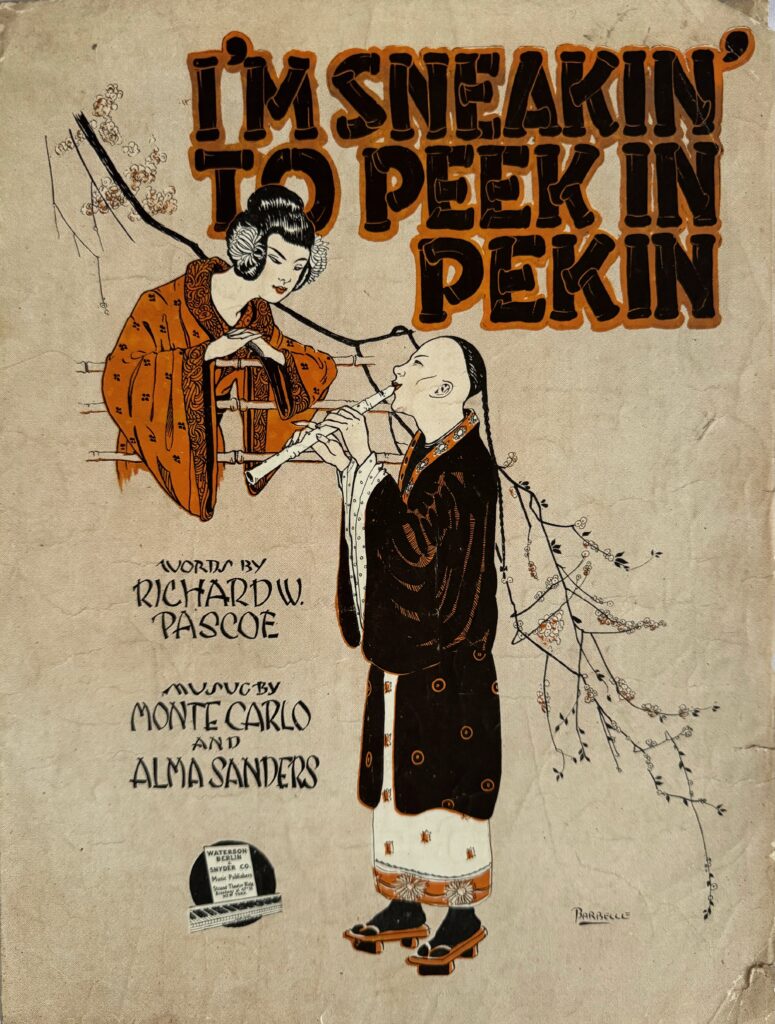

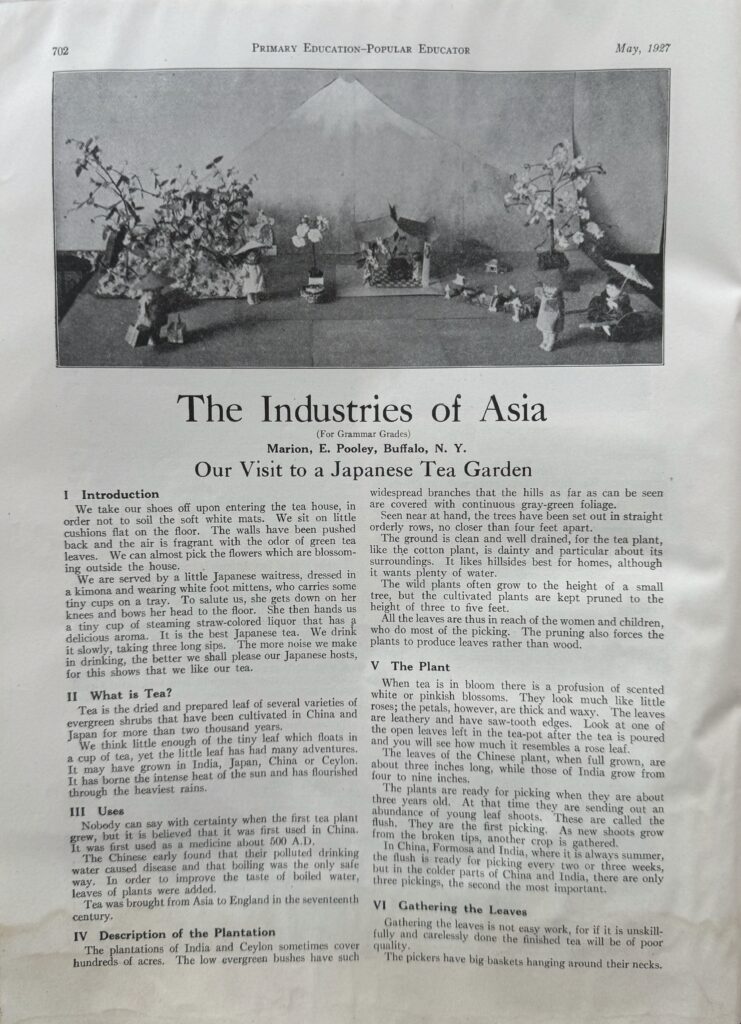

Considering the elementary age of the French Primary School students and the abundance of remaining art supplies and sheet music, we suspect creative activities were also explored. A curious abundance of sheet music with inaccurate lyrics about Far East life are set to punchy tunes and feature unusual cover illustrations. Here, we see more blending of cultures in mismatched clothing, shoes, prints, and hairstyles, noted by UNF Professor of Chinese Language and Culture Meilian Lu. The Primary Education magazines utilized for the school published articles by teachers such as “Japanese Project in a Platoon School,” “Cherry Blossom Time in Japan” with directions on how to wear a kimono for girls and boys, and “The Chinese Play in Seattle.”

Left to right: “I’m Sneakin’ to Peek In Pekin,” Waterson, Berlin & Snyder Co., New York (1919) sheet music inside and cover; “The Industries of Asia” from Primary Education, Educational Publishing Company (May 1927).

Reparative Descriptions and Community Collaboration

I’ve asked my all community partners the same questions about the above items, plus their philosophies on chinoiserie and japonisme designs, cultural appropriation, and sensitive content—how do you address culturally sensitive items in your collection? What are you doing to educate your own audience on cultural appropriation and reparations? When is an object “too offensive” to be publicly accessible? Has collaboration with other organizations been fruitful in your research? Do you have successful examples to share that RAP could learn from? For the members of the AAPI community, I asked them how archivists like myself can be an ally.

Silver Claw-Foot Teapot with Stylized Dragon Finial, Reed & Barton, late 19th century.

In summary, the overwhelming, overlapping message I have received from everyone thus far: Hiding these items away for fear of controversy is not the way. Rather, wide, public education on the context in which non-Western materials were originally produced and acquired and the rightful context in which we should view them today will unite us. Working together, holding space for others, is the best path forward for uplifting under-represented peoples. Huh reflected, “I think a lot of what you’re showing is hurtful and cultural appropriation, but I also think it’s important to talk about and educate… We are a much more global world and should rely on each other. Back in the 19th century, we were all about colonizing and dominating peoples. We never imagined the world as it is today.”

The contributions of my community partners will be used to write the first iteration of archival descriptions of the highlighted items by the end of this calendar year, viewable in both our “mini-museum” where some materials are on display for Buckland House visitors, as well as our digital catalog, currently available upon request and hopefully online in the near future. A very sincere thank you to my collaborators, a list that continues to grow. A common phrase in our profession is: the work’s never done. This project has proven the cliche to be not so cliche. It is RAP’s earnest intention to present this special collection with the most respect toward the cultures from which it originates, informed and updated by ongoing research and expert consultation.

The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine),

by J. M. Whistler, c. 1860, in the Peacock Room, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art.

Thank you to my generous community of collaborators:

Rachel Bradshaw, Registrar, Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens

Emily Cottrell, Jacksonville Archivist

Jennifer Grey, FSCJ Library

Kelsi Hasden, Researcher & Writer, Jacksonville

Mitch Hemann, Archivist, The Ritz

Young Huh, Interior Designer, New York

Meilian Lu, Chinese Professor, UNF

Elena Øhlander, Visual Artist, Jacksonville

Imani Phillips, Jacksonville Public Library

James Rodgers, Collections Manager, Morikami Museum

… and growing

Bibliography

Balzac, Honoré de. L’Interdiction. Paris: La Chronique de Paris, 1836.

Boucher, Brian. “The National Archives Museum Is Under Fire for Allegedly Scrubbing Difficult Historical Events,” November 6, 2024,

news.artnet.com/art-world/national-archives-museum-under-fire-2564854.

Buck, Pearl S. The Good Earth. New York: John Day Company, 1931.

Chai, May-Lee. “The Missing Images of Chinese Immigrants,” October 23, 2018, www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/10/23/the-missing-images-of-chinese-immigrants/.

Forbes House Museum. “Opium: The Business of Addiction,” May 2, 2025, www.forbeshousemuseum.org/digital-opium-exhibit/.

Hocking, William E. Re Thinking Missions: A Laymen’s Inquiry After One Hundred Years. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1932.

Jacobson, Dawn. Chinoiserie. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2007.

Kane, Suzette. “Misguided China Idealists: Lessons from American Missionaries for Twenty-First Century China Analysis,” September 12,

2023, hamiltonian.alexanderhamiltonsociety.org/issue-three/misguided-china-idealists-lessons-from-american-missionaries-for-twenty-

first-century-china-analysis/.

Kwun, Aileen. “Opinion: It’s Time to Rethink Chinoiserie,” May 27, 2021, www.elledecor.com/life-culture/a36548998/time-to-rethink-

chinoiserie/.

Mohl, Raymond A. “Asian Immigration to Florida.” In Far East, Down South : Asians in the American South, edited by Raymond A. Mohl, John E. Van Sant, Chizuru Saeki. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

Momaya, Masum. “Ten Principles for an Anti-Racist, Anti-Orientalist, Activist Approach to Collections.” In Active Collections, edited by

Elizabeth Wood, Rainey Tisdale, Trevor Jones. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

Moon, Iris. Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2025.

Richardson, Erin. “Does the Museum Need Another Wagon Wheel Without Provenance?” In Collections and Deaccessioning in a Post-Pandemic World, edited by Stefanie Jandl and Mark Gold. London: MuseumsEt, 2021.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Sloboda, Stacey. Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

Waldek, Stephanie. “The Complex History of Chinoiserie,” November 17, 2020, www.housebeautiful.com/design-inspiration/a34693915/history-of-chinoiserie/.

Wichmann, Siegfried. Japonisme: The Japanese Influence on Western Art in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Harmony Books, 1981.